Election Day, 1990

A tale of simpler times, and the poem I wrote about Trump when I was twelve.

I never had Election Days like I did when I was twelve. Jesus, does anyone?

It is November 6, 1990, and I’ve let myself into my next-door neighbor’s house. I know they’re awake. My best friend’s stepfather had left bluefish on our front steps, wrapped in foil. He liked to go ice fishing before dawn. I was a fellow early riser, and I listened for the drop, wanting to get the fish before the cats did.

My best friend lived next door. She was one year older than me, almost to the day, and our names rhymed. We considered this to be fate.

When she moved in, I was seven and desperate for a friend. My sister, a year and a half younger than me, had claimed the neighborhood girls as her own. I was shy and it speaks to my loneliness the lengths I went to make sure the new girl was mine.

“Can the girl who lives here come play?” I said when the door opened. It was 1986 and a snow day. Her mother, who I realize in retrospect was only 27, told me to wait. A few minutes later, an eight-year-old appeared, covered in scarves and a purple snowsuit. I could only see her eyes, but they were friendly, and lonely like mine.

“I’m Sarah,” I said. “I live next door. Do you want to go sledding?”

“Yes,” she said, and from that moment on we were best friends.

Now it was 1990. I was 12, and she was 13. Somewhere over the summer, childhood had ended. The neighborhood kids used to gather for big group games — Spud, Red Rover — that were really sanctioned excuses to beat on each other. We had played our last game in August 1990, but I didn’t know it.

You never know the last time you pick up your child, or the last time you play with your childhood friends. If you knew it was the last, you’d hang on harder.

I peered into my best friend’s room. She was sleeping under a collage of posters of Bret Michaels and Axl Rose and Sebastian Bach. I eyed the clock with concern: it would take her at least an hour to spray her bangs.

“Get up,” I said, throwing a pillow at her head. “It’s Election Day. There’s no school. Let’s go out. I’m going to play Nintendo while you get ready.”

She had a Nintendo and I had an Apple IIc with Oregon Trail. We routinely broke into each other’s homes to play each other’s games.

“I have to do my hair,” she protested.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah,” I said. “Do it faster.” I settled on the floor to rescue Zelda.

She put on the radio, which spat out socially conscious songs of doom. George Michael’s “Praying for Time”, Poison’s “Something to Believe In”, Phil Collins’ “Another Day in Paradise”, Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car.” It was normal in 1990 for Top 40 radio to bemoan the death of the American Dream.

I could hear her blow dryer on blast, which meant we were getting closer. I didn’t bother doing my hair: it’s naturally wild, like 1990 had laid down permanent claim. I was wearing a black denim jacket that I wore for 16 years, until I got pregnant in 2006, and it no longer fit. I wore sunglasses, not because I was cool, but because it meant I didn’t have to look anyone in the eye, and no one could tell when I’d been crying.

My best friend emerged in a Hypercolor shirt and double denim and her bangs sprayed so high, I burst into song.

“Can you take me high enough,” I crooned, “to fly me over your hair-sprayed bangs?”

I was parodying the new Damn Yankees song. “Can you take me high enough? It’s never over; yesterday’s just a memory—” I continued, until she slugged me.

We were out the door. We had a routine and there was no discussion needed. We went to Quik Pik to buy our horoscopes, which came in long rolled up papers, each a dollar. We assiduously guarded the knowledge of these mighty scrolls. It was the start of the month, so there was a new one laying out our November future.

We were both Virgos so we figured we were subject to the same fate, destined to stay together, and ignored every difference in our lives in order to believe this was true.

“‘A new love will appear,’” she read. “Good!”

“You already have a million loves.”

“I need a million more.”

“Your Hypercolor shirt is gonna have a lot of handprints.”

I put our horoscopes in the secret inside pocket of my denim jacket, which I used to avoid getting my stuff stolen when I got jumped as a kid, and later in life, to hide my money from gangsters in authoritarian states.

We kept walking, past the closed ice cream shack, past the gun store, and past the pharmacy, which was my favorite place, because it had been my childhood candy shop and was now my preteen library. I sat for hours in the magazine rack, reading for free and buying gum for penance. The owner let me, because it was hard for a 12-year-old to afford the volume of reading materials I required, and I wasn’t bothering anyone.

The only problem with the pharmacy was that it was in front of the projects. This is where the kids who liked to beat us up lived. I never figured out why people wanted to beat me up so badly, and I’m 46 and still living with this quandary. I didn’t get good at street fighting until I learned that to win, I’d have to go feral, stunning my opponent with raw audacity. After that, they left me alone. But at 12, I read my Rolling Stones with a wary eye on the door and kept constant watch on the streets.

Our parents didn’t know where we were, and we didn’t know where they were. Work, probably. It was of no concern. We had babysitting money, and we were going to blow it all at our local paradise: Burger King Palace.

Burger King Palace was the only reason kids from other towns envied where we lived. It was an experiment by the Burger King corporation to get in on some Chuck E Cheese action, with the result that a sprawling, anarchic indoor child’s playground was in walking distance from my house.

Burger King Palace was incredible. It should have been a UNESCO landmark. The Palace was shaped like an enormous castle with turrets and towers. If you ate in a tower, you could drop French fries on people’s heads and run down the back stairs before they figured out who did it. The dining room was next to a cavernous game room, which had a twirly slide, a ball pit, Skee-Ball, dozens of arcade games, and a stage where terrifying animatronic monkeys sang “Chantilly Lace” and “Yakety Yak” in distorted death-tone drones. You could have your birthday party in the back room with those monkeys, if you were brave enough.

In the front were machines that converted cash into useful currency — tokens — and tokens into tickets you got from Skee-Ball triumphs. Those tickets could buy a prize worth ten times less than what you spent winning it, but the labor was what counted. My parents raised me to have a work ethic and clearly this is what they had in mind.

I won enough tickets to get a neon green slap bracelet that said U CAN’T TOUCH THIS.

“If you take the plastic cover off,” my best friend said, “you can have a razor, and cut people with it.”

“Yeah, I know. I’m getting it in case we need a weapon.”

“That’s smart,” she said. “You’re always thinking.”

Outside Burger King Palace, kids were dealing drugs. I was a graduate of the DARE program, which presented drugs as a menu of hallucinatory appetizers to sample, resulting in my classmates Just Saying Yes. I am possibly the only 1980s child to actually keep their DARE pledge.

Teenage dealers waved us over. My best friend wanted to go because she thought one of the boys was cute. I talked her back inside, into the safety of Burger King Palace, where childhood went on, protected, until the money ran out.

By the time we were done, the dealers were gone, and I was glad. I also wasn’t worried about money. We were highly sought after babysitters, entrusted at age 12 with the care of infants, for which we were paid two dollars an hour.

I had a babysitting job scheduled for Friday night, and I was excited because I could raid the father’s Stephen King collection. I had just finished Pet Sematary, my first King book, and it scared the shit out of me.

“If I died,” I asked, “and you could bring me back to life, but I wasn’t the same as before, would you do it?”

“Not the same how?”

“Like I’d look the same, but I’d act different. I’d maybe act really bad. Really mean.”

“Isn’t that how everyone is already?” she asked, and we were quiet, because it was true.

We decided to walk to where a skateboarder my friend was stalking lived, to see if we could get a glimpse of him. On the way, we counted the cars that honked at us, two girls aged 12 and 13, and we felt flattered. It didn’t occur to us to be offended, much less afraid, because their approval contradicted the cruelty we faced at school.

“I love Election Day,” my friend said. “I like no school for no reason. We can do whatever we want and everyone leaves us alone.”

“It’s not no reason, it’s so grown-ups can vote in the gym.”

“They can have the gym forever,” she said. “I never want to go back.”

It was the last week of fall. The trees were burnt orange and pale brown, glimmering in the high hills surrounding our city. Fall felt crisp no matter the weather, a sensation long gone by. I don’t know if it’s because 25 years ago I moved halfway across the country to a different climate, or because seasons no longer exist anywhere. I associate that autumn scent with freedom, with sunlight that shone after supper, with friends who stuck around when the cold days came.

Earlier that year, 1990, I read a letter in the local newspaper. A man wrote that he knew our city was a hellhole, rife with drugs and gangs and crime, and that everyone was right to complain — but had we taken the time to notice how beautiful the hills were? That they surrounded us at every turn, the result of the city being inside an ancient volcano? How lucky we were to live in this gorgeous geology — one that would never change no matter how bad life got?

I had never noticed. But I noticed it every day after, everywhere I went. That man has no idea the impact of his letter. If he hadn’t written it, I might have turned out differently. Now I seek out the best parts of the worst places and treasure them.

I try to do it with people, too, but that’s a tougher task.

We wandered past Election Day signs advertising candidates. I don’t remember much except that Lowell Weicker ran for governor as an independent, which seemed to piss everyone off, even though he won. He had his own party, called “A Connecticut Party,” which was even funnier, because Connecticut parties sucked, especially ones hosted by guys named Lowell.

“I’m never voting,” I said, “because they’re going to send us to war.”

The Gulf War loomed large in my mind. I had a mix tape from the radio where “It Must Have Been Love, But It’s Over Now” was rudely interrupted by announcements about Saddam Hussein invading Kuwait. But it was more than that. The war scared me in a deep way — the power, the lust for blood, the way the news played it like an action movie.

I worried that the Gulf War would never end, because I knew about Vietnam. I was pleasantly surprised that spring when it did — and terrified, a decade later, when I realized I was wrong.

“Voting, war, whatever,” said my best friend. We walked past the video store, which was covered in posters of Julia Roberts dressed as a prostitute. The streetlights were coming on, which meant we should go home.

“Let’s run!” she exclaimed, and we did, for no reason. No one was chasing us, but it felt like something was, and it felt good to run together. It still feels like something is chasing me, but nowadays, I walk alone.

We turned onto our street, spiky chestnut shells littering the sidewalk, and slowed, panting. I put the shells in my jacket pocket with my slap bracelet: more weaponry.

“What do you wanna do now?” I asked. She ticked off a list of boyfriends she planned on calling.

“Oh,” I said, disappointed. These plans did not include me. “I’m going to write something. I’m writing a satire poem.”

“What’s that?”

“It’s when you make fun of someone, but like in a smart way. Like The Simpsons.”

“You’re going to be a famous writer,” she said, with the enthusiasm she carried like sunlight, shining it on everyone she met. I basked in it like it was a foreign substance, grateful it would shine on me.

“And you’re going to be a famous singer.”

“I’m headed to number one,” she agreed.

We used to sing songs from whatever sheet music I had. Our prized possession was a copy of “Greatest Hits of the 1980s” I found at a tag sale, but anything would do: Elton John, Cole Porter. My mom’s childhood collection of 1960s hits: “Mack the Knife”, “Bobby’s Girl.” As long as we were singing together.

Her voice was lilting and sweet, and mine was terrible, so I played piano. We recorded ourselves on a boom box, and she sent our tapes to record labels that she insisted would respond. When she was seventeen and eight months pregnant, I found an old cassette of us singing, our voices full of dreams, and felt a pang.

My childhood dreams came true — but in the worst way. I wrote bestselling books, all buoyed, in some way, by the election of Donald Trump. Sometimes I swat this monkey’s paw. How would I react if someone had thrown this hypothetical to me on Election Day, 1990?

You will become a successful author — but in return, Donald Trump will be the president of the United States and try to rule it like a dictator.

I’ve had enough conventional success to know true happiness doesn’t lie there, so I’d like to think I’d reject this temptation and spare the world.

Because I long knew the danger. The poem I wrote that Election Night, that satirical poem, was about Donald Trump.

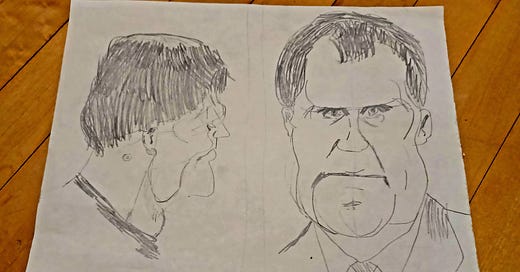

It was a parody of “The Night Before Christmas” detailing Trump’s cheating and bankruptcy. An excerpt of my seventh-grade opus:

Trump spoke not a word, but went straight to work

He looked at his money and screamed like a jerk

“My money! It’s fake! I’m almost broke!

I have nothing left! My life is a joke!”

He started to cry, which I thought was funny,

All he cared about in his life was his money!

“Material things shouldn’t matter at all,”

I said as he glumly stared down the hall.

He didn’t understand a single thing about life

Which is why he kept his money and threw out his wife…

In 2016, I remembered I had written it, because so many adults were feigning amnesia about how awful Trump had been, and I could not fathom why they didn’t share and express the same memories as me. I didn’t find the poem until last year, in a box in my mother’s basement. By then, it felt too late — but a lot of things about America did.

“Yesterday’s just a memory,” I sang to my best friend from my front porch as she turned the key to an empty home.

“Stop singing that song!” she laughed. “Damn Yankees suck!”

She ended up moving to Nebraska. I moved to Missouri. Neither of us went back, and we never will. We didn’t plan it that way. It was fate, like our names and our horoscopes. We only talk on Facebook, but in my heart, she is still my best friend.

And you know what? She was right: Damn Yankees suck. Especially the Damn Yankee running for office, the one whose crimes I’ve been documenting for 34 damn years.

My 1990 poem below:

* * *

Thank you for reading! This newsletter is funded entirely by voluntary paying subscribers. That allows me to keep it open to everyone and I don’t want to paywall in times of peril. If you like what I do, please subscribe! This is my job and how I pay my bills and support my family.

My middle school yearbook photo. I really shouldn’t have been talking shit about other people’s bangs!

More of my amazing seventh-grade wit.

So I was trying to figure out what motivated a 12 year old to write a poem about Trump in 1990… a quick search brings up an August 1990 Barbara Walters 20/20 interview. Side note, she dated Roy F’ing Cohn in college, are you kidding me?

Every piece you publish hits me right in the heart. Thank you 🙏