From Oklahoma City to Trump

Abandonment and accountability on the anniversary of the attacks.

The following is an excerpt from my new book, The Last American Road Trip. You can order it here and get a signed copy here.

***

On the first day of our Route 66 trip, the media announced that Donald Trump would be indicted that week. I did not believe them because I had heard this claim every year since 2016 and throughout my 1980s and 1990s childhood, when reporters were more straightforward about his ties to organized crime. Trump had been under federal investigation since before I was born.

The year 2023 marked a half century of the Department of Justice opening an inquiry and then doing little about it. With every year his impunity grew, and with it his cruelty. He pushes and pushes, as if frustrated with the ability of the United States to contain its worst instincts, which are embodied in himself. He pushes and pushes, as if testing whether people are as weak and hypocritical as they seem, and no one in power pushes back, which means he is probably right. Trump ended the week he was supposed to be indicted by holding a fascist campaign rally in Waco, Texas.

I knew the rally was coming, and I knew why he chose Waco. When the ATF stormed the compound of cult leader David Koresh in 1993, killing eighty-two people, including twenty-eight children, I was fourteen years old. I remember the shock of coming home from school and hearing almost everyone had died, and starting to cry. My mother initially assumed I was crying about Koresh and thought I was crazy, but of course it was not over him: it was over the deceived, the innocent, and the torment they endured. I had been following the case, and I could imagine how terrifying it was inside that compound for a child besieged by multiple forces. It seemed the cruelest way to die.

I was upset by the coverage because the media kept implying it was wrong to grieve people killed by the government. We were told these were not casualties who mattered: the same lie I heard on television two years before during the Gulf War. I refused to accept that because every death matters — especially that of a child. I was a child myself, and it scared me to see the casual dismissal of the killing of innocents.

I look at the middle-aged men and women at Trump rallies, so different from me in many of their views, and wonder what they thought of Waco when they were young. If they saw the same callous reports that I did and felt the same disgust. And then I see them under the sway of another cult leader, a criminal politician with no regard for their welfare, one who feigns contempt for the very forces that supported him for a half century — the FBI and its institutional apparatus.

I wish they would leave him for their own sakes. I don’t like cults, and I can’t stand the government, but I loathe cults of the government most of all.

Oklahoma City is on Route 66 halfway between Santa Fe and St. Louis. It is a natural place to break up a drive for the night. I did not know that I would be in Oklahoma City on the day of Trump’s rally in Waco. I do not know whether, had I arrived on another day, I would have reacted differently to what I saw or if what hit me hardest was the brutal banality of American horror.

Sometime in the twenty-first century, a day with a fascist rally or a mass murder became just a day. I do not know the exact tipping point, only that I cannot stop searching for it, like if I knew where it started, I could undo it. I want to unwind our century and cut the cord, let that alternative America spin off into the darkness and live instead in the future that never arrived.

We arrived at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building Plaza as the sun was setting. We climbed up a stairway from the street and entered a platform overlooking a field filled with chairs made of steel and glass. Behind the field was a pool bordered by two hulking identical bronze archways. We walked down the stairs to the field and the sun hit the chairs, making them glow, and the sun dropped behind the archways, making them dark, and the pool reflected everything. The pool reflected everything: 168 chairs to represent 168 victims, the archway with “9:01” engraved on it to signify their last moment of peace, the archway with “9:03” engraved on it to signify the first moment of recovery, the redbuds blooming in defiance, the sun flooding the field with its final light. The pool reflected everything like a parallel reality, a before and an after, the future and the unfathomability of its erasure.

At the Oklahoma City National Memorial, you are left forever contemplating time. You are left forever wanting 9:01 to come back.

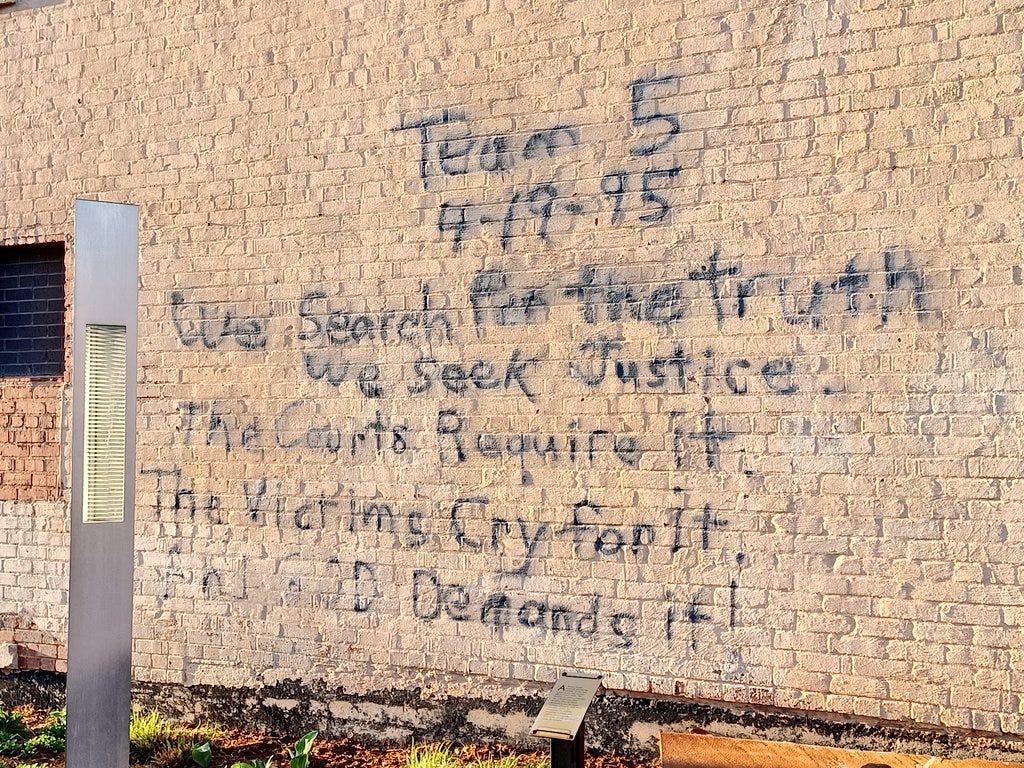

On the side of the pool is a building with a spray-painted message: “We search for the truth. We seek justice. The courts require it. The victims cry for it. And GOD demands it!” It was written by an Oklahoma City rescue team member on April 19, 1995, the day that Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols committed the deadliest domestic attack in American history by blowing up the Murrah Federal Building and much of the surrounding area with a truck bomb. The building on which the message was painted was one of few that remained; it is now a museum about the bombing. McVeigh claimed the attack was in retaliation for the ATF siege at Waco on April 19, 1993, exactly two years before. He expressed no remorse that his own attack had murdered children. In the memorial field, there are nineteen small chairs to represent the nineteen children he killed.

After the attack, the children of Oklahoma City drew pictures. Those pictures are now preserved in tiles on a wall. They drew rescue workers and families holding hands. They traced the outline of their state and drew hearts and Band-Aids inside. They called Oklahoma “the broken heartland.” They struggled for words. “I feel very sorry,” wrote a twelve-year-old. “I’m sorry,” wrote a ten-year-old. “Fix the hurt,” one child wrote in small, wobbly print.

I walked back to the pool, where my husband was standing with my children, all with tears in our eyes. My children knew the history of the bombing. But it is one thing to know it and another to be where it happened. My husband and I were overwhelmed, even as adults who had lived through terrorist attacks ourselves. But I was grateful that our children, who had seen so much horror in their short lives, could see the memorial because what they had not seen enough of in America was compassionate commemoration. They knew all too well that life could change in an instant, but they had rarely seen an official declaration that it mattered, that we should grieve together as a nation, and that acknowledging the pain can make it hurt less.

I wanted them to know that this was America too. That there was a time, not that long ago, when it was considered so important to remember the dead that a stunning memorial would be created in their honor. That of course Americans from across the country would grieve for Oklahoma. We live in an era of mass violence and pandemics and a government that tells us to move on, to look away, to abandon each other, to weaponize our pain for their politics. They tell us that we brought this upon ourselves. But ordinary Americans have not had the power to bring things upon ourselves for a very long time.

This is not a partisan matter but the prevailing attitude of American institutions. The line from the Waco siege to the Oklahoma City bombing to Trump’s Waco speech is a circle. McVeigh and Nichols were part of a network of domestic terrorists that the federal government did not investigate, one that remains active today. The refusal to investigate spanned every administration, Democratic and Republican. The officials who participated in that obfuscation have been installed in office for decades.

It should not be children writing on walls that they are sorry. It should be them.

That refusal of officials to atone for horrific mistakes, to confront their own failures and hold the perpetrators accountable, is how rare acts of violence and extremism became common. Americans are told to abandon the pursuit of truth because truth forces accountability, and accountability reduces fear. It is easier to control people who live in constant terror — not only of violence but of apathy. The fear of being killed, and being forgotten.

The Oklahoma City National Memorial is designed to make you appreciate life as you honor those from whom it was stolen. It is impossible to visit and believe that America is beyond redemption. Because good Americans never forget the victims. They never abandon them, even in the darkest hours, even when there seems no light ahead, because they are the light.

***

Thank you for reading this excerpt from The Last American Road Trip. I am on tour and will be in Austin on 4/15 and Tulsa on 4/16. If you’re in the area, please come to the events! I’ll be taking questions and signing books. Here is my full tour schedule.

Dear subscribers: I will return to writing articles here once my book tour ends. I have a lot to say, so get ready! I am planning a Q & A and more. Thank you for your patience and support. I do not paywall in times of peril, and this newsletter is supported entirely by volunteer paying subscribers. If you like my writing, please consider a paid subscription! It pays my bills and ensures my work is accessible to all.

All photos taken by me in March 2023, which is also when I wrote this chapter.

Get the book while my books are still allowed.

I remember being horrified by Waco and saying a government should never use military tactics against it's own people. My brother, a militant atheist, said, "But they were religious loonies!" Which was when I got, on a deeper level, that whether you like someone or not has no bearing on what is acceptable to do to them, but a lot of people think it does. I was more shocked by Waco than by Oklahoma City, even though I was a leftist and generally pro- government. Or maybe it's because I was pro-government. Good guys have to be held to a higher standard.

I was in high school in the waning days of the Vietnam War. My generation did not serve—by the time our boys got close to the draft age Nixon was bringing the troops home—so I was surprised by my reaction to the Vietnam War Memorial in DC. I cried as I walked down the smooth black surface, reading name after name. So much death, and for nothing. We do remember. We do honor. Americans are not depraved, or at least not any more than any other people. We lose sight of what matters. We are swayed by rhetoric and the rhetor delivering it. I hope I can go to the Oklahoma City memorial one day. I’ll have your essay by my side. Thank you, Sarah.