How to Get Lost

Rejecting the world in favor of humanity

I descended into the woods at noon and did not emerge for hours, and every mile I walked, I walked alone. I was in a land the exact acreage of Central Park and there was not a soul to be seen. That was the way Don Robinson envisioned it, and I am the beneficiary of his wish.

Robinson was a St. Louis inventor who became locally famous for selling a stain removal product on late-night infomercials. He also became rich. In the manner of rich people, he began buying up land. In the manner of Missouri eccentrics, he bought unfarmable land in the Ozark foothills. He loved the terrain he called “wild and wooly”: box canyons and gnarled roots and trees so large and primitive you expect to see dinosaurs strolling by.

An acquaintance of Robinson’s described him as “a conglomeration of every weird off the wall thing that you’ve ever dreamt about or seen and every nice thing all at the same time.”

Don Robinson wore ragged clothes and shoes held together with duct tape. He bought groceries with coupons and favored canned soup. He lived in a ramshackle, moss-covered cabin without regular heating that still stands. He lived alone but let strangers explore his sprawling backyard. I know Missourians who grew up roaming his property, splashing in creeks and sliding down sandstone, on the lookout for a legendary weirdo.

Robinson stopped buying acres once he matched the size of Central Park. He never said why he did it. But when you see photos of New York’s manicured lawns surrounded by luxury apartments, you understand.

Before he died in 2012, Robinson willed his entire property to the Missouri State Parks system. He explained he had to do it before his “melon-headed cousins from out of nowhere come out of the woodwork and sell the joint.”

It was a story that fit his curmudgeonly persona. But behind the scenes, Robinson set up a trust so the park system could keep his land wild and free in perpetuity.

On a hilltop near the park entrance sits Don Robinson’s grave. There are always birds fluttering around it, like they knew he did them a favor.

On Thursday, I left for the park, car keys in hand. My keychain has a bullet that says SARAH on it. I bought it in a Texas gift shop in 2019. I figured if there is a bullet with my name on it, I was going to own it. I got a lot of death threats that year.

Now we all get a lot of death threats. You needn’t have angered anyone in particular. There is a new bullet, and it reads HUMANITY. Pandemics and climate catastrophes and world war, backed by plutocrats who view loss of life as a gain for their agenda.

They brag about the employment rate because they have given you all new jobs. Your job is to acclimatize yourself to their dark ambitions. Your job is to accept a vicious hierarchy in which some lives are deemed disposable, in the hope that you will be spared. Your job is to back the winning side, which is the killing side, under the illusion that they will have your back when your time comes.

This is a lie. There is a target on your back and the winning side put it there. They will deny it if you ask. They will say it’s a logo, a brand. But a brand and a target are the same thing.

Powerbrokers pretend elite criminal impunity is transferable to the masses. They promise you can live like them if you play along. This is how vigilantes end up headlining GOP events and crooks get liberal media puff pieces. This PR crusade is demoralizing, but demoralization is not the main objective. The quality they seek to cultivate most is envy; and from envy, inclusion; and from inclusion, a façade of safety.

The end result is complicity. But people in political cults do not realize that until it is too late.

That the powerful would try these tactics was inevitable. There was an Anomalous Era of American Accountability brewing between 2017-2020, and it had to be destroyed. They had to break the bonds of revulsion Americans felt toward extreme criminals like Jeffrey Epstein or the Sackler opiate dynasty and annihilate shared disgust at the collaboration of political parties against the public good. They had to do something about the widespread pandemic revelation that, yes, the powerful will leave everyone to die.

Their answer was to convince us that we should kill each other instead.

The destruction of humanity is a bipartisan project, bolstered as much by inaction as by crime. Government refusal to enforce accountability for criminal elites has emboldened ordinary citizens to commit violence believing that they too will get special protection. It has created cults of placation who tell you that justice is a prize of the privileged, that politicians exist to be worshipped, and that citizens who demand accountability are the real fascists.

This is why I wander into the woods alone. For hours of reprieve at the edge of a season, when the leaves blaze brightest right before they fall.

Don Robinson State Park is less wild and wooly than when I first went after it opened in 2017. Back then, the paths were barely marked. I would get lost and end up at the bottom of a canyon, debating whether I wanted to climb out. I would get distracted by an unusual lichen and take hours to relocate the trail. I carried a paper map and no phone. The park did not have cell service, which is another reason I liked being there.

Today Don Robinson is a mildly popular hiking destination where park rangers scrawl notes on the first trail marker. The latest one said “Tree-Hugger Hippie”. I don’t know if I fit the bill. There is a fine line between a hippie and a slob. Twenty years ago, my husband tried to figure what I was, since I meet some criteria but not others, until he realized I did not understand there were criteria to be met, nor would it occur to me to meet them. I’m not rebelling, I’m existing, which makes for an unpleasant surprise when people voice their objections.

In the woods, I don’t worry about that. Don Robinson State Park is a sanctuary for slobs.

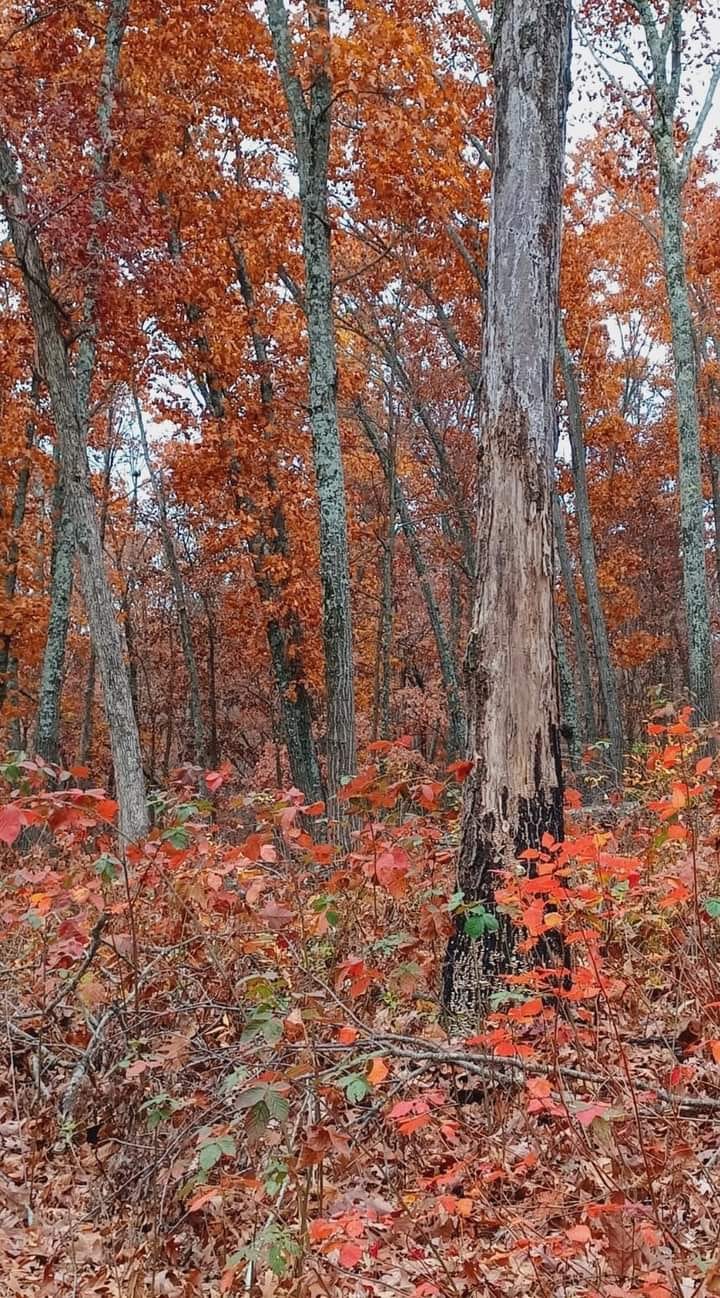

This week the park reminded me of my early explorations. Enough leaves had fallen to bury the trail, making it inaccessible to the uninitiated. By now, I can walk the trails of Don Robinson blindfolded, but why would I do that on this rare day -- the special moment on the calendar when the sky turns sepia interrupted by spectacular red and gold? Trees shone like technicolor holdouts refusing to concede to a black and white movie: barren and gray but for their defiant branches. It was cloudy, and the absence of direct light only intensified the brilliance of the leaves that remained.

There is no bad time to visit Don Robinson, including the dead season. In winter, the bone architecture of the canyon appears, and icicles hang like teeth. If you are lucky, frost flowers follow. In the spring, I hunt for morel mushrooms, because the soil should be right, but I have never found them there. (Like any morel hunter, if I had, I wouldn’t tell you.) In the summer, I look for wildflowers and hide in the canyon from the heat.

I have seen a lot of wonders in that park, but none matches the reliability of solitude. I’ve learned that what leaves you alone is better than anything you could find. It is safe to cast your burdens down there because no one can throw them back in your face.

On a dark day in 2022, as an endless canvas of trees and boulders and no human life stretched before me, I yelled “I’M FREE”, because liberation felt like sharing pain without a witness. I craved the dead echo of inanimate spectators. They kept an eccentric old man company in his day, and then they took care of me, too.

* * *

On Thursday, my pain was grief. I looked at the colored leaves dwindling at the edge of a branch. They reminded me of the last people of conscience, the holdouts to a world that has declared empathy an affront.

I watched the leaves drift to the ground and tried to decide whether it was surrender or a deserved reprieve. They had done their job, and now they would feed the soil. They would hide the path so that strangers had to explore, instead of walking a rote and worn road.

The leaves on the ground forced onlookers to navigate their surroundings. The leaves on the trees made visitors notice how precious and beautiful they were and hope they would stick around a little longer.

I lied when I said I liked to be alone. I like the company of my memories, and the dreamy desire for memories of the future.

When I am in the woods, I think of other people and wonder what their special places are, where they go when they are sad. And then I think of the lands from which so many are displaced with impunity, the sanctuaries destroyed by military force. I cry in the woods for the future that was stolen and wish I could offer a piece of my own.

And then I leave, knowing when I return, nothing will be the same, most of all me. I will retrace my steps and wander off the trail and walk through my pain until it is possible to process, and I will never take that prospect for granted.

* * *

In a 2009 interview, Don Robinson described what inspired him to purchase the land in the 1960s. “I just didn’t want to, you know, have neighbors, for God’s sake,” he said, shuddering, a mischievous glint in his eye.

I stop by his burial site before I go home. He has lots of neighbors now. One lit a candle until its wax dripped into a pool of blue. Another wrote “RIP bro” on a stone and put it on his grave. Birds chirped and squirrels scampered, because they are his neighbors too.

I don’t like the idea of heroes, not only because they betray you, but because they bore you. But I seek consolation same as anyone, and I find some in this kindred spirit, who rejected the world in favor of humanity.

Who told everyone to get lost, and meant it, in the best of ways.

Don Robinson State Park, Missouri. Photographed November 9, 2023.

I recently read somewhere, “Trauma is not just what happens to you, it is also what didn’t.”

Your beautiful essay is rich with this duality. As a lifelong roamer of remote beaches, i recognize this kind of solitary journey. There is some comfort in facing even the darkest truths, empathy pulls one there to bear witness. Only then, having faced the worst, can honesty emerge and perhaps hope with it.

I love this piece. Featureless wildlands are glorious, but so difficult to describe. Your ability to write about the land in such a moving and graphic way is a treasure. Thank you for this.