Death Valley was alive.

I had heard rumors, but it is one thing to imagine and another to see. There are not usually fields of flowers in Death Valley, the hottest place on earth, but it happens from time to time.

There is not supposed to be a lake in Death Valley. But it happened, because time has twisted and turned, and offered its redemption and revenge.

I went to Death Valley because Earth is on life support. I wanted a place where time is so vast that you don’t need to borrow it.

I wanted confirmation that we are living in hell, and Death Valley delivers. Its toponyms beg you to turn back: “Funeral Mountains”, “Coffin Peak”, “Dante’s View.”

I like this straightforward inhospitality, this steadfast disregard for mankind. Beauty posing as bleakness, so that no one gets too close. Death Valley had rejected humanity before humanity could take its best shot.

That’s what I thought, anyway, before I saw the water.

* * *

I was in Death Valley for a family vacation and because I was on the run. There should be a more normal way to put this, but there is nothing normal about my life or my country, so why pretend.

There are a large number of people who regularly remind me that they intend to kill me, and not much I can do about it. If they don’t protect judges and rich people, they sure as hell aren’t protecting me.

Sometimes an uptick in death threats collides with my children’s spring break. I have learned to see these weeks off as an opportunity to disappear to places where I can see the stars, and no one can see me.

We get on the highway and blast Del Shannon — “If we gotta keep on the run, follow the sun!” — and I sing loud and pointed, a joyful yearning bitter freedom, like a dagger poised at the dawn.

My children had never been to California. The farthest west they had gone was Arizona, where a 2023 trip to the Grand Canyon was derailed by an atmospheric river causing catastrophic floods. I had been to California for work on other people’s dime, but only to the coast. I had never been to the desert, even though of course I had seen it, like every American child, in movies set in galaxies far, far away.

California has an otherworldly feeling that goes beyond its landscape. Many stores no longer take cash, an impediment to my surveillance dodge. Even the skies are captured by robots. When you gaze at the Milky Way from California’s remote terrain, Starlink appears like a dotted line dividing our divine primordial past from a future designed by Elon Musk.

It is easy to be paranoid in California, but hard to outwit The Man. Bat Country has morphed into Big Tech Dystopia. Maybe it is not as terrifying as it seems, if you are used to it.

Maybe people getting used to it is the terrifying part.

In the border town of Pahrump, Nevada, we stocked up on supplies for Death Valley. Pahrump is full of brothels and bitcoin; Nevada’s past and future scams. We passed a military-style complex which had, inexplicably, wild horses roaming in front of it. We pulled in to discover it was a city park.

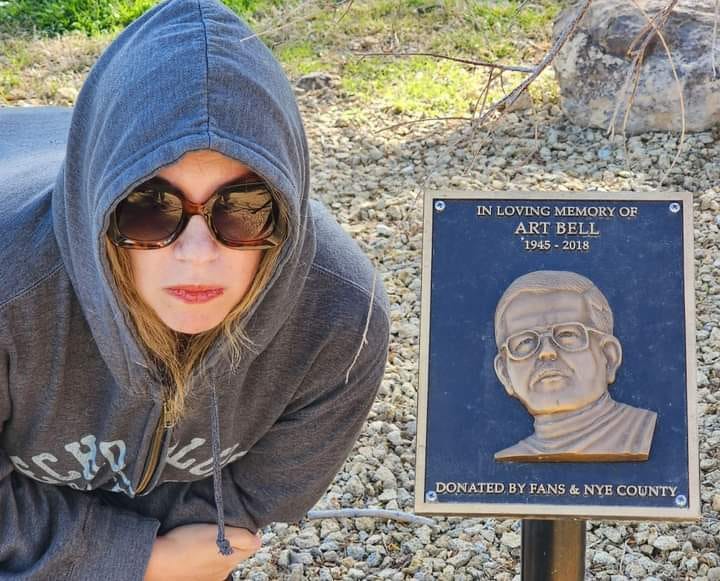

As my children watched the horses play, I found a familiar face on a park bench plaque. It was a portrait of Art Bell, host of Coast to Coast AM, a radio show popular with people interested in government conspiracies.

I liked Art Bell when I was younger because he never dismissed anything as crazy out of hand. If the caller sounded deranged, he wanted to know why, and would hear them out, for better or for worse. He was a relic from a time when it was harder to decontextualize ruminations on conspiracies and weaponize them for politics and profit.

Pahrump was Bell’s base of operation during his 1990s peak, and he had returned before he died in 2018. His fans commissioned a memorial for a curious man who had become a curiosity himself.

It made sense that Art Bell was from Pahrump: a border zone between the lawlessness of Las Vegas and the impenetrability of Area 51 and the illusions of Los Angeles.

A road stop to a wasteland where, even though it could kill you, you at least knew what was real.

* * *

We had left Missouri during a spectacular season: early spring, when dogwoods and redbuds bloom and I spend my days scoping out the sycamores on south-facing slopes for morels. We had traded it for brown desert mounds and dirt, and even in my excitement, I missed the lushness of my life.

But there is a continuity between Missouri and Death Valley, and it is geology. I went from a state with some of the oldest boulders in North America to another ancient zone, and when I saw California’s billion-year-old rocks, I felt at home.

We are one continuous nation, no matter our faults.

Death Valley is the largest national park in the contiguous United States. It is also the driest, the hottest, the lowest, and the most dangerous. There is no cell phone service. GPS frequently falters and some roads are impassable unless you have a vehicle designed for ultra-rough terrain. Unprepared travelers are hospitalized in the summers, when temperatures have reached as high as 134 degrees.

As a result, Death Valley’s beauty lies in its endless mountains and craters and minerals: a geological vortex with almost no habitation. This is what the world looks like stripped to its elements. Rocks undulate in waves of color, surrounding you on all sides. Glittering borax and puzzle-piece breccia draw you close; marbled mountains beckon from afar.

The first major site you pass upon entering Death Valley is Zabriskie Point, a long-dead lake made of waves from every shade of gold you know and some you did not realize existed.

The sun is your enemy in Death Valley. But it is also your guide, giving you a different view of the same site hour by hour, its shifting shadows rewarding your mind’s eye. You could stare at Zabriskie Point all day and never get bored.

Past Zabriskie Point, near an area called Furnace Creek, 200 feet below sea level, wildflowers appear. Fields of gold on black rock, a rebuke to the notion of a dead land.

It is hard for me to envision Death Valley as dead, when it rids me of everything I despise in the world. To be free of outside threats — to be free — is nothing I take for granted. Death Valley felt alive because it let me live. The risks I took there were ones I chose, not ones imposed from on high by way of deception.

But I wanted my children to see Death Valley bloom. To know that life can persist in the harshest conditions, that barren lands are more generous than they seem, that walking through the valley of the shadow of death can be a pleasant stroll so long as you’ve got good company.

It is easier to teach them this than to teach them to love the dead rock world for its durability. That’s a lesson for later in life.

Scattered flowers are common in a Death Valley spring. Some years, after heavy rain, there is a “super bloom” covering the park in color. That didn’t happen this year, but I didn’t mind. I grew up examining wildflowers in sidewalk cracks, and now I saw them on an epic scale. Slender stems standing strong in piles of shards, defying the odds.

Death Valley is a good place to defy the odds: you are, by definition, starting from the bottom, as low as a person can go. You become accustomed to every extreme, yet never unphased by the grandeur.

But what I wasn’t prepared for, in any way, was the water.

* * *

Badwater Basin is the lowest point in North America, 282 feet below sea level. It is endorheic, meaning that it is not supposed to retain water. Under normal circumstances, it looks like a field of white salt laid out in a grid of interlocking honeycomb shapes that extend to the mountains on the horizon.

I wouldn’t know, though, because I saw a lake instead.

12,000 years ago, Badwater Basin was home to Lake Manly, which was about six feet deep. 10,000 years ago, it disappeared.

In 2024, it came back.

While the return of Lake Manly was not entirely unheard of — it made a fleeting shallow appearance after heavy rain in 2005 — it had never been so deep in modern times that people could kayak and swim. That’s what visitors had been doing in the month before we got there.

They could do this, perversely, because of climate change. The same type of atmospheric river that had derailed our Arizona trip the year before had returned in February and filled Badwater Basin until the lake reemerged, five times saltier than the ocean.

In early March, 60-mile per hour winds blew Lake Manly two miles from where it had formed. The lake that was not supposed to be there in the first place had pulled a fast one. No one knew how to process so many natural phenomena relocating on their own volition. Rangers decided to curtail the kayaking. Who knew what trick the lake would pull next?

We knew that Lake Manly would be there, and we were excited to see it. It was an unprecedented event.

But there is nothing to capture the feeling of walking into something so wrong and so right at the same time. So beautiful in its visage, and so devastating in its implications.

When my son saw Lake Manly from the car, he asked, “Is this what Death Valley is going to look like in the future? Because of climate change?”

“What’s more likely,” I said, “is that the rest of the world is going to look like Death Valley.”

Everyone got quiet. But the mood changed when we arrived. In the distance was something between a miracle and a ghost.

Mountains reflected on a double-edged magic mirror. Soaring peaks are exotic for us on their own; we are Midwesterners, after all. But on an ancient lake, reborn in Death Valley? A rapture, a rupture: it was almost too much beauty to bear.

We walked to a beach of what looked like white sand, but we soon realized was salt. My husband hung back, but my teenage children could not resist the lake’s lure. They took off their shoes and ran barefoot to the water, and I ran alongside them.

My daughter, a fast-moving loner, raced toward the horizon. I let her go; she was like me when I was young. I waded with my son, the thick water rising until it covered our ankles and approached our knees.

The area was popular by Death Valley standards. But the more we walked, the more alone we were, to the point that we could look in three of four directions and see no one but ourselves, two foggy phantoms in a lake that should not be.

Humanity was behind us, and ahead loomed a void: an ancient resurrection, a freakish novelty. We would either never see Lake Manly again or it would return regularly after more catastrophic storms. Neither prospect was reassuring.

In 2022, my neighborhood experienced a once-in-a-millennium flood in which many lost their homes. The same once-in-a-millennium flood hit two other states later that month. Across the world, people have endured record heat, record floods, and record cold. Weather catastrophes that used to strike once a century now arrive with disconcerting regularity. The oceans are warmer than ever before.

I stared at the lake and made up a story. The mourning earth had wept so hard, it made a lake of saltwater tears. I was wading in a warning. I held my son’s hand and focused on the present: the past and the future were wrapped inside it anyway.

We moved into deeper water and the salt got sharper, cutting my feet as I walked over it. I didn’t realize how bad it was until I got back to shore and mopped up the blood. I had been punctured and punished for my curious ways.

At the time, I took the pain in stride. I was in a special place and my son was with me. Whatever happened to Lake Manly, I knew we would never get this moment again.

The mountains seemed to get more distant even as we got closer. The salt formations started to slash our legs, too, and the sting was too much. We turned around. This wasn’t a place for people.

When we reached the shore, my daughter was ecstatic. She had never seen such an amazing sight and I told her I hadn’t, either. I looked at the three of us: bleeding, laughing, covered in salt and mud. My children are teenagers. I don’t know how many more family vacations we have left, for a variety of reasons.

I put on sunglasses so they could not see my tears. I did not know why I was crying. Happiness and fear, relief and apprehension. I was crying with the lake and for the lake: the lake that should not exist, the lake that thrilled the world with a return without warning, the lake destined to transform until it is only a memory, like far too many things.

* * *

At night we went to the Mesquite Dunes. This is where they filmed the original Star Wars: we were on Tatooine, Luke’s home planet. We lay on our backs and waited to see the Milky Way. It arrived, even with a full moon rising. Death Valley is an international dark sky site. I’ve been seeking those out since the world got bad and my life got scary, because dark skies always stay the same.

Except for that night, when I saw Starlink slither its way across, and suddenly this galaxy did not feel like mine. A Death Star had interrupted my reverie.

Nothing can fully destroy the joy of the Milky Way. But you are supposed to watch the sky; the sky is not supposed to watch you back. I know why Lake Manly jumped two miles, I thought wildly. Like all of us, it’s on the run.

This summer, Lake Manly will wither away. It will revert into a brimstone oasis, and people will burn themselves on land instead of cutting themselves in water.

There’s a lesson in this gorgeous, unforgiving place. Keep your distance — because true distance is a blessing, and a rare find, these days.

Keep your distance, and hold it close to your heart.

Thank you for reading! My newsletter is made possible by voluntary subscribers — I do not paywall in times of peril! If you like my writing, please consider a paid subscription.

Death Valley in bloom, photographed March 2024.

Noted Star Wars spot! I hear there is a wretched hive of scum and villainy nearby…

A nutjob conspiracy theorist, and also Art Bell.

Scum and villainy!

The salt of Lake Manly.

Tatooine…er, Mesquite Dunes. (And yes, I know that Star Wars was also shot in Tunisia, don’t come at me, I’m just a simple soul going to the Tosche Station to pick up some power converters!)

"We are one continuous nation, no matter our faults."

You know, that's a masterpiece transitional sentence you wrote, tying in the geology with the social. It's one you should be very proud of, and I bet you are! :)

Hi Sarah,

Your writing is beautifully touching, especially with the contrastingly harsh subjects that draw you and your family’s interests. I hope you’re always keeping a few salty tears in your eyes, including your mind’s eye, to protect your vision, perspective and sense of being as a critically important part of something even grander. There is a silver lining to being “on the run” in search of peace. There is a special sense of belonging within the solitude, even when amongst your closest loved ones. When challenging our deepest beliefs and preconceived notions of how the universe works through experience, we better understand ourselves as a small yet important part of this universe.

I have often saved your articles in a growing list of “Favorites” so much so that it has devalued the essence of the word. Your work and efforts are shaping and developing more than just you and your family. I have no doubt that many of your readers have become more knowledgeable, thoughtful, insightful and compassionate to the world we find ourselves in. Thank you for everything you’ve done and stay safe on your remarkable journey beyond your comfort zone.

With kindest and deepest respect,

Jonathan Jay Stec