It was the 30th of December, and I was driving the Natchez Trace Parkway, looking for Bobbie Gentry.

I didn’t want to find her. I only wanted to know she was out there, eluding everyone.

I wanted her to outwit every man who did her wrong. Many are dead: Bobbie Gentry is in her 80s. She hasn’t appeared on stage since 1981, when, after a series of music industry disputes, she left public life behind with a steadfastness unrivaled.

I was not the first to explore Chickasaw County, Mississippi and other Gentry haunts, hoping for a glimpse of the singer. For over forty years, no stranger has tracked her down. Gentry wanted to disappear and she got her way. She is rumored to be happy. I am likely angrier about the treatment of Bobbie Gentry than Bobbie Gentry is.

It’s only fair when a trailblazing woman gets burned that younger women pick up the torch.

In 1967, Bobbie Gentry destroyed the Summer of Love. The Beatles crooned “All You Need Is Love”, flower-haired hippies swayed — and in July, Bobbie Gentry released “Ode to Billie Joe”, a spare acoustic ballad about a suicide whose true horror was the politesse and apathy which with it was greeted.

What America needed was not love. America needed truth served cold and clever. “Ode to Billie Joe” framed cruel indifference as mystery. Americans ate it up like a southern noontime dinner.

Ode to Billie Joe knocked Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band off the top spot. It made Gentry, who wrote and sang the title track, a massive star. The genre-defying hit — “I don’t sing white or colored; I sing southern,” she explained — dominated the Hot 100, country, easy listening, and R&B charts. Gentry was indefinable, independent, and confident in her dark lyricism.

As a result, she had to be punished. America loves to blame the messenger, especially when the message presages darker days. Some believe the flower power era ended with the Manson murders. “Ode to Billie Joe” suggests the sunny sixties never existed.

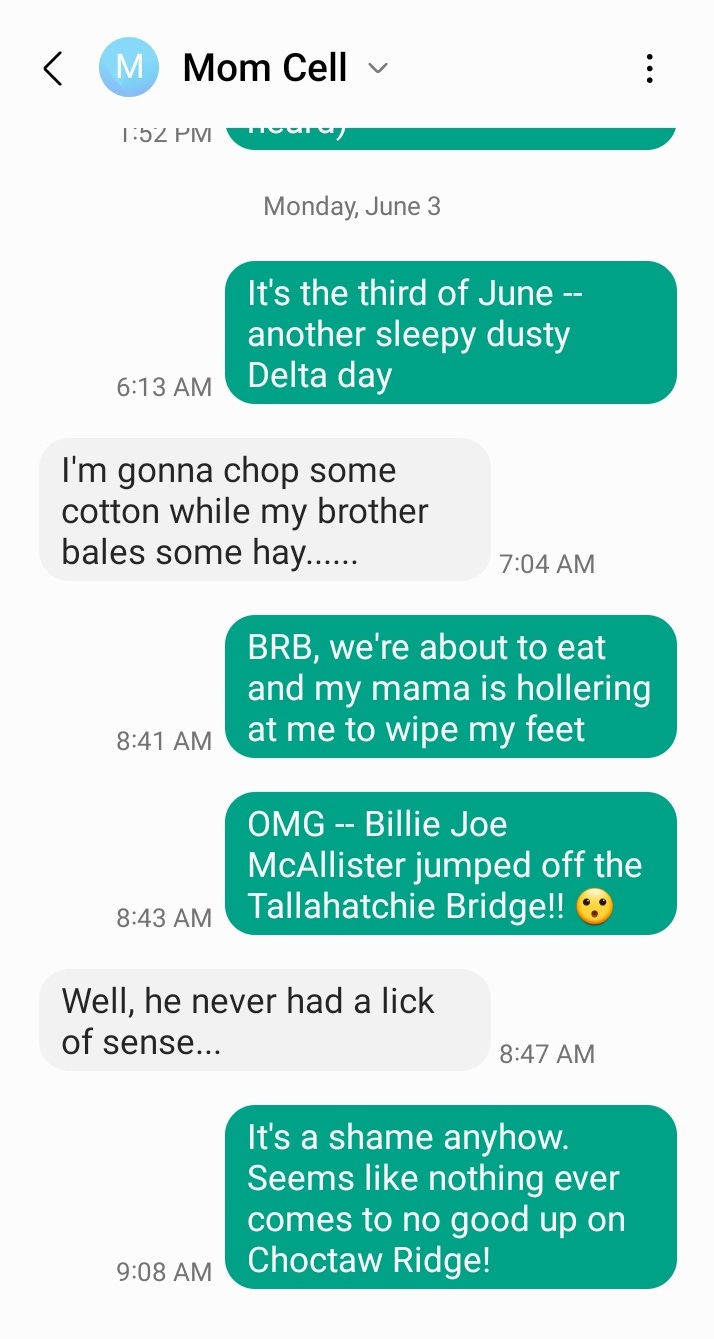

“Ode to Billie Joe” is the first-person tale of a family eating dinner on the third of June, “another sleepy dusty Delta day.” They are discussing Billie Joe McAllister, a local boy who died after jumping off the Tallahatchie Bridge. Later, it is revealed that not long before his death, a preacher saw Billie Joe throw something — never named — off the bridge while accompanied by the female narrator of the song. The family members portray Billie Joe’s death as inevitable (“Nothin’ ever comes to no good up on Choctaw Ridge”) and unimportant.

They care more about their meal than his suicide. The song’s most chilling line is “Pass the biscuits, please.”

The parents do not notice how Billie Joe’s death shakes the narrator. In the final verse, it is a year later, and she spends her time throwing flowers off the Tallahatchie Bridge. During that year, “There was a virus goin’ ‘round and papa caught it and he died last spring, and now mama doesn't seem to wanna do much of anything”.

She recites these horrors like a grocery list.

* * *

In the years after 2020 — when covid ravaged America and protests raged over the brutal murder of George Floyd, only for both tragedies to ultimately be abandoned in favor of apathy — I listened to “Ode to Billie Joe” hundreds of times.

The Summer of 2020 was no Summer of Love. But it was a summer that was supposed to mean something. The next few years were aimed at convincing us that it didn’t, and that we were foolish to believe it would. The real crime was compassion. The real crime was noticing and caring and wanting to make it right.

The biggest villains, in the Biden years, were the messengers: epidemiologists and activists and documentarians of tragedy battling a brigade of pundits and politicians who wanted us to pass the biscuits, please, and ignore that body under the bridge.

* * *

One would think that after “Ode to Billie Joe” — a commercial success and lyrical masterpiece housed in the University of Mississippi library next to Faulkner — Bobbie Gentry would be allowed to do whatever she wanted.

To believe this is to not understand how women are treated in creative industries. When a woman has an unconventional hit, the reaction is often to try to contain her, even sabotage her. Success does not protect female writers — not even from their own publishers.

Instead of gaining support, Gentry found her abilities questioned. “I am a woman working for herself in a man’s field,” she told an interviewer in 1974. Reporters insulted her intelligence. Men took credit for her ideas. She was entangled in industry lawsuits, which she won. She became so wary of management contracts that she limited them to six months to ensure her freedom. Every career move was a tightrope of painstaking navigation and vindicated paranoia.

Her follow-up, The Delta Sweete, was true to Gentry’s vision: enigmatic ballads, raucous soul, and dark southern covers, including “Sermon” (popularized by Johnny Cash as “God’s Gonna Cut You Down”) and “Parchman Farm”, about the notorious Mississippi prison. The US press largely ignored the album and it sold poorly.

“No one bought [The Delta Sweete] but I didn’t lose any sleep over it,” said Gentry in 1968. [1] I don’t know whether to believe her, but I’m glad she said it.

When America lost interest in Gentry, she became the first female songwriter to host a variety show on the BBC. She often co-directed, but the BBC would not give her formal credit, and she left.

When America regained interest in Gentry, she headlined Vegas revues and partnered with Glen Campbell, becoming an Americana sex symbol and a southern gothic intellectual all at once. A bandmate described her as “an overpowering presence” who micromanaged her elaborate shows [2]. In Vegas, she married a rich man 31 years her senior and divorced him four months later, making lots of money. She signed on to an “Ode to Billie Joe” movie, making lots of money again.

Enough money to vanish in style.

The 1970s brought the voluntary end of Gentry’s career and some of her best songs. In 1969, she headed to FAME Studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama to record Fancy, released in 1970, under the production of Rick Hall, one of few men to consistently champion her talent.

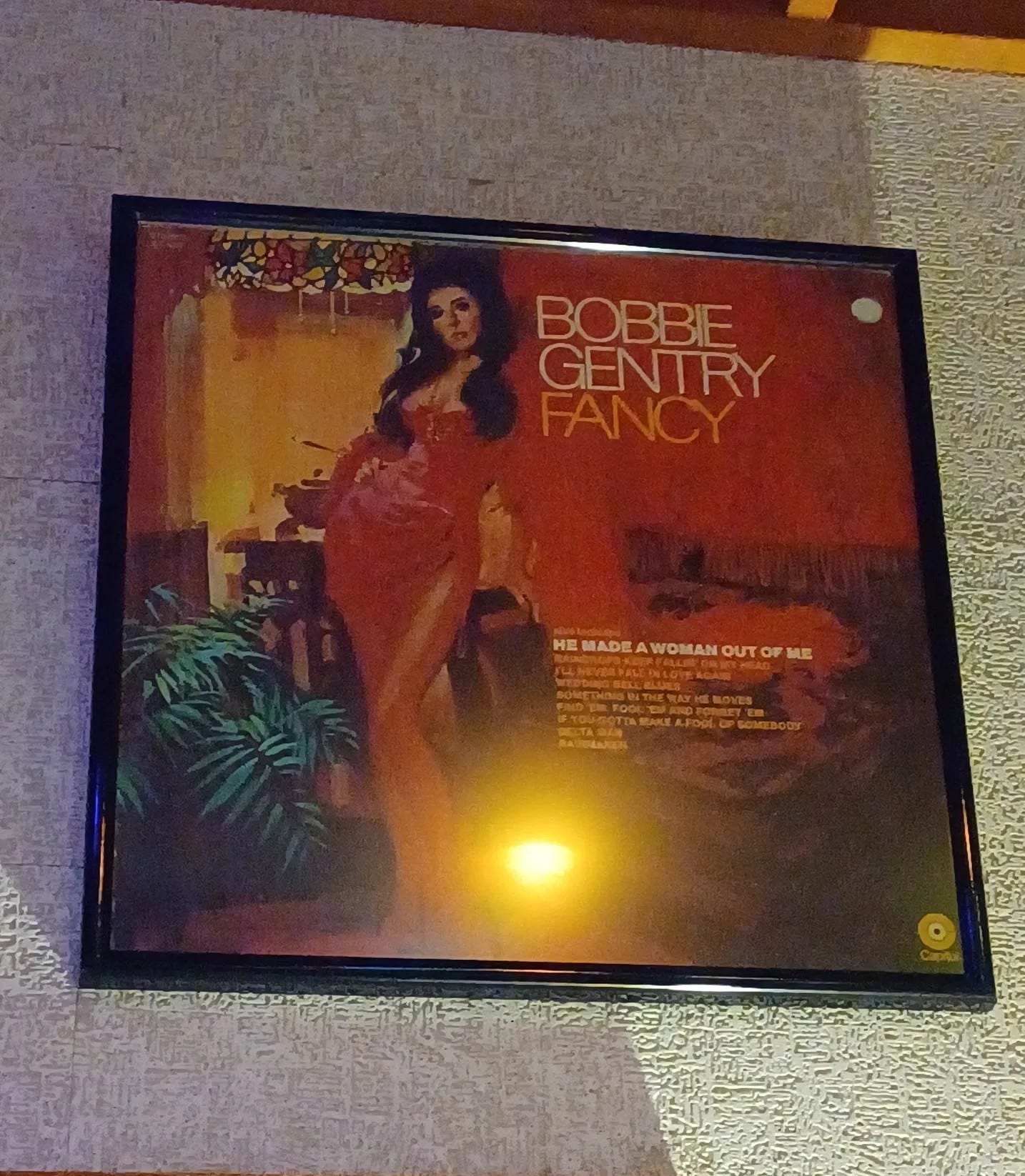

While on book tour this April, I visited FAME. I stood under the Fancy cover: a painting of Gentry wearing the red velvet high-slit gown of her album’s protagonist, a teenage girl named Fancy who slept her way out of destitution and into independence, unrepentant about doing what she needed to survive.

The tour guide played “Fancy” in the very room where Gentry recorded it. I felt like I was seeing a ghost, but it was the indomitable spirit of the song: Gentry’s second and final hit. Like Fancy, Gentry rewrote the rules of a rigged game before she quit it.

Gentry’s 1971 album, Patchwork, was another commercial failure. Produced solely by Gentry, it alternates between character vignettes; musical interludes; and wry, sad confessions — in particular, the closer, “Lookin’ In”:

I'm packin’ up and I'm checkin’ out, I'm on the road again

Feelin’ like I'm in a pantomime

But the words will come to me in their own good time

Tumblin’ and stumblin’ over in rhyme

And the ugliest word that I ever heard, my friends, is sacrifice

It’s an easy out for all you should have been…

She never made another record.

* * *

Bobbie Gentry was so ahead of her time that she had to leave it.

She sang of the south, where she was raised. She lived in Greenwood, Mississippi in 1955, the year Emmett Till visited and was murdered by racists who threw his corpse in the Tallahatchie River. Gentry was thirteen, a year younger than Till.

Was “Ode to Billie Joe” inspired by Till’s murder? No one knows. Gentry refused to reveal what was thrown off the bridge, believing it incidental to the indifference expressed in the face of tragedy. Scholar Kristine M. McCusker hypothesized that the song reflects changing attitudes of southern whites — including whether to show guilt — at the time Gentry penned the lyrics.

“Ode to Billie Joe” reflects 1955 and 1967 and 2025. American cruelty masquerading as respectability is timeless. What’s hard to fathom today is a cutting social critique becoming a mainstream hit. The music industry has been drained of its power to reflect the people, despite Gentry’s themes resonating now more than ever.

This is particularly true since 2021. The pandemic “ended” when officials decided to bury public health data: another sleepy Delta covid day. Sedition went unpunished until public memory became blurred enough to rehabilitate a coup plotter. Promises made in 2020 to end racist police brutality were not only broken but mocked by the very politicians who made them. (In one particularly grotesque example, Nancy Pelosi thanked George Floyd for dying.)

On social media, anyone could join the callous chat. Americans mourning loved ones were berated. Americans hit by natural disasters were told by distant strangers to “just move.” Americans stripped of rights were ignored by former allies. Emotional breakdowns in public places were filmed and posted online so that a person having the worst day of their life could have an even worse one. Americans were told they deserved what they got and what they got was horrific: the agony, and the apathy.

Cruelty was incentivized for profit and boosted by algorithm. Good-faith arguments could not happen when both “good” and “faith” had vanished. But Americans were not supposed to discuss that: not in a way that acknowledged collective pain. We were told to “move forward”, politician code for “turn your back”. Move forward, they implored, justice is divisive to the unjust.

Gentry is foremost a storyteller. Her songs are not overtly political. But tragedy feeds politics, and politics breeds tragedy, and Americans have been both the predators and the prey. There are few who convey the cruelty of abandonment, and its maddening ambiguity, like Bobbie Gentry.

“Ode to Billie Joe” is known as a sad song. But its sadness lies in the absence of mourning. Death came and people shrugged. If they grieved, they grieved alone.

* * *

In December 2023, I belted out Bobbie Gentry songs as I drove through her name-checked towns of Kosciusko and Okolona and Tupelo. I took in the lay of her land, imagining it in her time. But it is still Gentry’s time: it will always be Gentry’s time. In America, every day is the third of June.

Over the last four years, as cruelty flourished and creativity fell under fire, I turned to Gentry. She didn’t compromise; she didn’t cut and run. She outwitted the industry that sought to suppress her. She had faith that her work would endure after she left the stage — and it did. Gentry destroyed respectability and then did the most scandalous thing of all: abandoned fame for freedom.

[1] Quote from Tara Murtha, Bobbie Gentry’s Ode to Billie Joe.

[2] Quote from Tara Murtha, Bobbie Gentry’s Ode to Billie Joe.

* * *

Thank you for reading! I would never paywall in times of peril. But if you’d like to keep this newsletter going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. That ensures every article remains open to everyone. I appreciate your support!

“Now in this world there's a lot of self-righteous hypocrites that would call me bad…”

Inside FAME Studios, Muscle Shoals, Alabama.

The Natchez Trace Parkway in Mississippi, one of my favorite drives.

The Natchez Trace is, of course, haunted.

A Mississippi swamp that grows rock and roll.

My mom and I get a little silly every June 3…

Your writing is breathtaking. Your words carve out a niche in both heart and mind then fill those spaces with . . .something. And yet (probably because of this), I have to prepare myself, steel myself, to read what you write. You knock me off center, Sarah. You pull up blinds, clean the glass. Provide meaning and context and change the way I look at life in the country I was born into 69 years ago. I do not find you easy to read, but I am grateful for every word.

Your attitude and writing, it seems to me, sums up life in the US of A. You hold on to the ideals and aspirations (that have rarely been realized) while navigating through the everyday apathy and casual cruelty of the place. It's amazing how you've formed such a level headed view of the country while living within it. I only achieved clarity after observing it from without when I left during the Reagan years. A friend summed it up once when he reacted to someone calling the US a melting pot; he said "more like a pressure cooker". Oh, and the 60s weren't really that sunny to those of us who lived through them. I was one of those you refer to as " hippies", a term we would never have used, and despite exuberance and hope that things were changing, our reality was assassination of MLK and RFK, brutally suppressed ghetto revolts, pollution, and hanging over it all was the senseless war in Vietnam. Thank you for continuing to call out the Mafia state for what it is.