I was going to make a noose, but instead I made a basket.

The basket coils like a snake in wait, white string binding plain brown rope. It is small but taut. When I rest it on its side, it looks like an eye. I put it on my bedside so it can watch over me as I sleep.

The basket is too small to hold anything but nightmares. But I know it’s working, because I used up all the rope for my noose.

* * *

I wanted to stab someone 8000 times. Instead, I cross-stitched an ancient design.

The design is a Mediterranean dream not my own. A four-square grid of dark blue and light blue: the cross, the star, the carnation, and the scroll, made of tiny x’s.

I like imagining that hundreds of years ago, a Byzantine craftsman stitched the same patterns as me. I do Palestinian embroidery, tatreez, for similar reasons. I want to learn from a past that persists to the present: a strike against genocidaires who insist that Palestinian culture never existed.

I also do tatreez because it’s attractive. Why is it so hard for some to see the beauty? Maybe this is not a question to ask of those who abide the mass murder of children. People who violate universal taboos are not going to understand art or life or love.

It takes me about a month to stab something 8000 times. To X out so much that my stabbing forms intricate shapes and the X’s blend into a restorative whole. From a distance, there is no X in the fabric at all.

I stabbed X so many times that a new and tranquil world took its place.

As I embroidered, Santorini — where I spent my honeymoon decades ago; Santorini, where the inspiration for this textile came — was evacuated due to earthquakes. I remembered riding a donkey by ancient ruins and eating octopus fresh from the sea, and my husband and I wondering when the Iraq War, then three months old, would end. By the time the war of lies was over, we were raising two children in a rotting husk of America, and Greece hated us with reason.

I dream of Mediterranean days. The soft blue thread makes me feel like I could still ride the waves, though I likely never will again.

I wove a cloth of rage, and when it was finished, I held a cloth of memory.

* * *

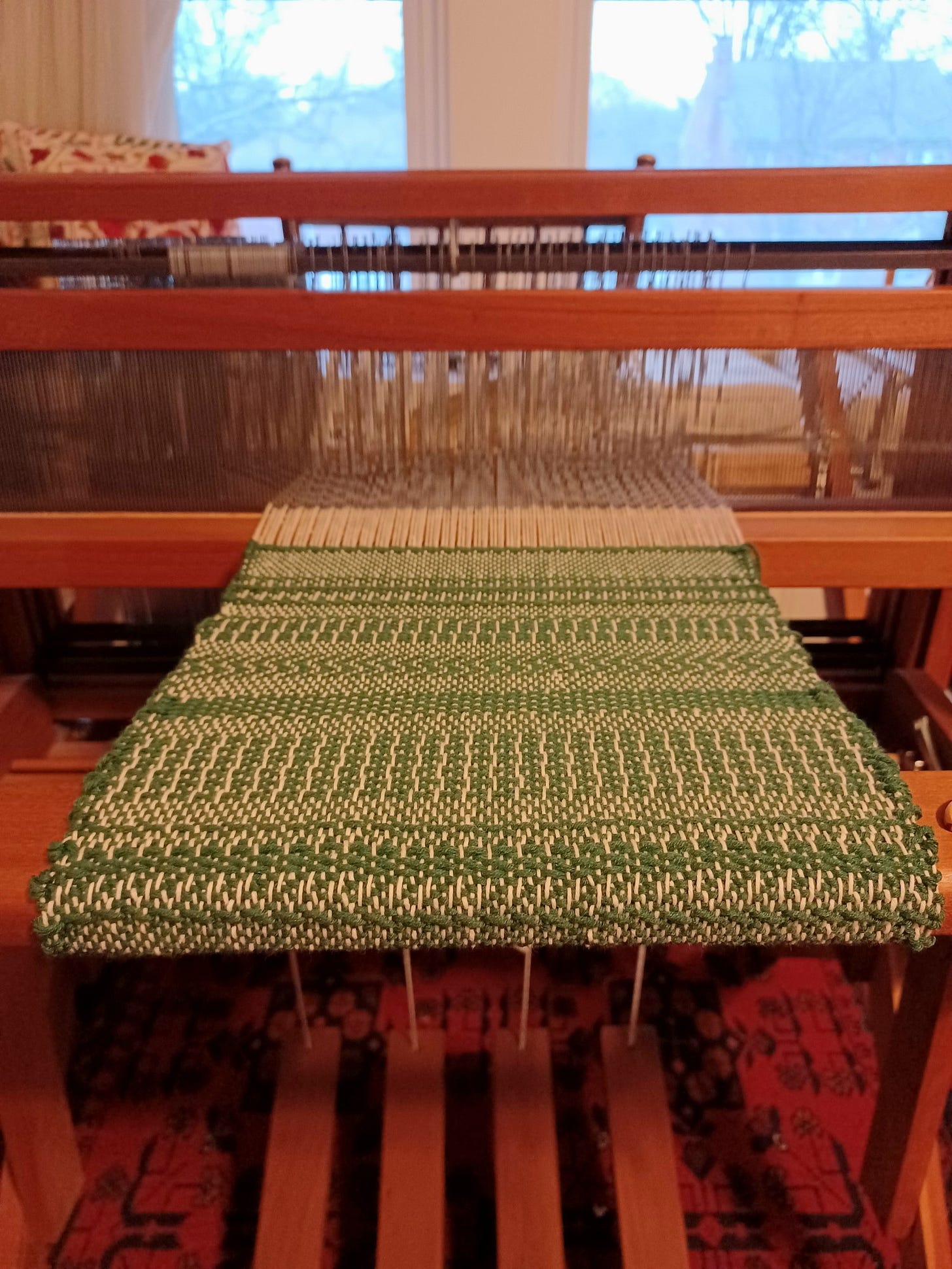

I wanted to beat someone to death, but instead I got a treadle loom. A loom is an ideal apparatus if you feel like murdering people but also making an appealing placemat.

The center part of a loom is called a beater. You slam it until you push the threads into submission. Before you beat the threads, you pull them through narrow metal slots, like prison bars for string, until they reach the other side. That thread is called “warp” because it takes a warped mind to create this contraption.

I am learning to weave from an 81-year-old woman who generously gave me her old loom and is teaching me how to use it. I asked her how to get the threads through the slots, and she informed me I would use a “slay hook.”

“Yes!” I said, wielding the s-shaped metal like a weapon until she gently told me it was spelled “sley hook”.

“I’m calling it a slay hook anyway,” I said. “Because I want to slay something.”

“Well, this part of the process is very boring,” she said, as I moved 120 strands of thread one by one, “so you might as well.”

I wondered what the spies using surveillance technology to track me thought of my new project. I hoped they were stuck watching my weaving lesson. I hope they groaned when they discovered that after pulling each thread through 120 tiny bars, I had to pull each thread through 120 tiny holes. I hope I bored them to death.

Excessive crafting is a standard Midwestern response to excessive stress. I would be a model Midwestern housewife if I didn’t despise these people with every fiber of my being, and some fibers beyond it.

* * *

The edges of woven cloth are called selvages. They hold the piece steady. I like practicing selvages because it is novel to have something I can keep from falling apart.

For weeks, I thought my teacher was saying “salvages”. A poem would enter my mind:

Time counted by anxious worried women

Lying awake, calculating the future,

Trying to unweave, unwind, unravel

And piece together the past and the future,

Between midnight and dawn, when the past is all deception,

The future futureless, before the morning watch

When time stops and time is never ending.

That’s from “The Dry Salvages”, the third of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets. Eliot lived in St. Louis, like me, though he considered himself an Englishman. He carried the Mississippi River on his mind, like me, and it entered his poems. I included an excerpt of the poem in my book They Knew, to the bewilderment of my editors, who saw They Knew as modern political history.

But “The Dry Salvages” belonged in that chapter. Now that the world has turned futureless, people no longer ask why it is there.

After I wrote They Knew, I went to Eliot’s house in St. Louis, which is now a parking lot covered in weeds. I sat next to a faded marker saying he once existed, and I smiled.

“Wipe your hand across your mouth, and laugh,” Eliot wrote. “The worlds revolve like ancient women/ Gathering fuel in vacant lots.”

I returned to my weaving teacher, a fellow anxious worried woman trying to unweave, unwind, and unravel. It turned out we had a mild loom error and a few drooping threads. We came up with the ultimate Midwestern solution: holding them in place with a Petoskey stone.

Petoskey stones are pieces of fossilized coral found on Michigan lakeshores. No one knows how much northern Michigan feels like Santorini. I can tell you only because I know you won’t believe me. The glory of the Midwest is that no one believes how gorgeous it is, so you can spill its secrets and still not reveal them.

Sometimes the best weapon is to be underestimated. History’s self-appointed winners have poor survival skills because they inherit power through family wealth and live in bubble worlds. They fear ingenuity because they have none. That’s why they build robots to tell them what to think and sell destruction as “disruption.”

The robots are supposed to replace us, not them. But only someone who wanted to be replaced would crave such technology. Men of scripted reality, men of cults and mafias, men who are nothing more than memes.

You see it in every empire, this dearth of creativity and its twin outcomes: wreckage and theft. We will feel our own misery as a result of theirs, which is why I’ve learned to make a basket when I want to make a noose.

* * *

One night I woke shaking from a nightmare that was a prognostication that became a memory.

I went to the loom and beat my anxiety into submission. I wove like people have woven since the dawn of time. Creating surfaces from strands, improvising designs, dissolving my sorrow into the fabric of history.

When I was a little kid, I taught myself to play piano, and I was very good. No one knows how I did it, not even me. But I know it had to do with numbers, and a system I invented that translates them into patterns and sounds and colors, inextricable and unexplainable.

They call it synesthesia. Until I was twelve, I assumed everyone had it. I was startled that others don’t see the world like I do — that all letters and numbers and musical notes have a color; that when a word is on the tip of your tongue, you see its blurred palette; that sentences have chords and keys, and you don’t choose them. They choose themselves and you translate the melody.

And that when you embroider or weave, all these incomprehensible practices merge into something normal that you can give to people as gifts.

Pushing the pedals of the loom, I felt eight years old again. Deciphering another ancient instrument, oblivious to a world that wants to kill me.

I am no longer oblivious to the world’s designs. Patterns reveal themselves even when I’m not looking. But I own a slay hook now.

* * *

I wanted to corral my enemies and twist them together into a prison of pain, but instead I made a basket out of pine needles.

When the world ends, I will have the most decorative apocalypse bunker.

Making a pine needle basket is easier than it appears. This was my first try, and while there are challenges to keeping the needles level, it comes down to strength and repetition. You pull tight with waxed thread, weaving in and out at an angle, adding new pine needles until the coils form a basket.

People worldwide have been making these for millennia. But the craft is particularly common among indigenous peoples of North America, whose coiled creations I see in indigenous territory in the southwest and in Oklahoma. I study them in museums and see them sold by contemporary Native craftspeople. Craftspeople who carried on their traditions in the face of genocide, passing them down to the generations whose existence the US government sought and failed to prevent.

There is a reason that the Trump administration is banning study of historically targeted groups — Native Americans, Black Americans — and it is not “DEI”. They do not want Americans to grasp the lengths to which this government will go to kill or to learn from the ingenuity and determination of those who fought back.

US government tactics and ideologies mirror those of Israel and apartheid South Africa. They also parallel the American past, but now the target list includes everyone.

* * *

Crafts are not the only things I make. I also write books that reveal the plans of transnational criminal plutocrats to destroy everything that makes us human.

Plutocrats who only get their hands metaphorically dirty and never touch the ties that bind. Who cut themselves off from the customs of humanity yet pose as traditionalists.

Who hang not by a string, but a pixel, with the world eager to hit delete.

I wonder what it’s like to be so hated. I know what it is to loathe and to fear. But I also know what it is to create with the simplest materials and tools. I know what it is to have a connection to humanity so intrinsic I don’t need to build a machine that mimics a friend.

I know that if these men destroy my books, my crafts may survive. Safe in anonymity, with no one knowing anything other than a human being cared enough to make them. That if I am gone, my children will have objects they can hold in their hands that were created with love by mine.

On the nights when the noose beckons, that has to be enough.

* * *

Thank you for reading! I would never paywall in times of peril. But if you’d like to keep this newsletter going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. That ensures every article remains open to everyone. I appreciate your support!

Finally, some big news: I have a new book! The Last American Road Trip comes out in April and is available for preorder: www.thelastamericanroadtrip.com. If you like the travel and history articles on this newsletter, you will love this book! Tour information is coming. Stay tuned!

The basket I made instead of a noose.

Pattern by Avlea, an excellent embroidery shop: Avlea Folk Embroidery.

Pedal to the heddle!

What, do you not have a Petoskey stone handy when your loom malfunctions?

My first pine needle bowl. The zebrawood centerpiece came from Becky’s Baskets.

So grateful for your courage, Sarah, in sharing the intensity of your rage (and thereby validating my own). Blessed be the messengers. Your creations are beautiful.

A beautiful weaving of words and emotions.