For two days, my sister and I had a secret shame.

“Are you concerned about the Walsh house and Dylan’s bungalow in the fire like I am or am I just weird?” she texted on Wednesday.

“If Casa Walsh burns,” I replied, “it will be my Notre Dame.”

I’ve never been to Pacific Palisades. But I feel like I have. Many Americans do, because we’ve been watching Pacific Palisades all our lives. We watched it in Carrie and Teen Wolf and Freaky Friday. It was the setting of Saved by the Bell and the rival town in Sweet Valley High.

When my sister and I were kids and discovered that Pacific Palisades was real, we were floored. We wondered from our post-industrial city what it meant to live out a California dream, how everyday life could be so charmed. We wondered what the people there were like.

The answer is human. Human and grieving as they navigate the charred ruins of their world, captured on camera in new and horrible ways. Envy turned to embers and empathy: Pacific Palisades is real, and it breaks your heart.

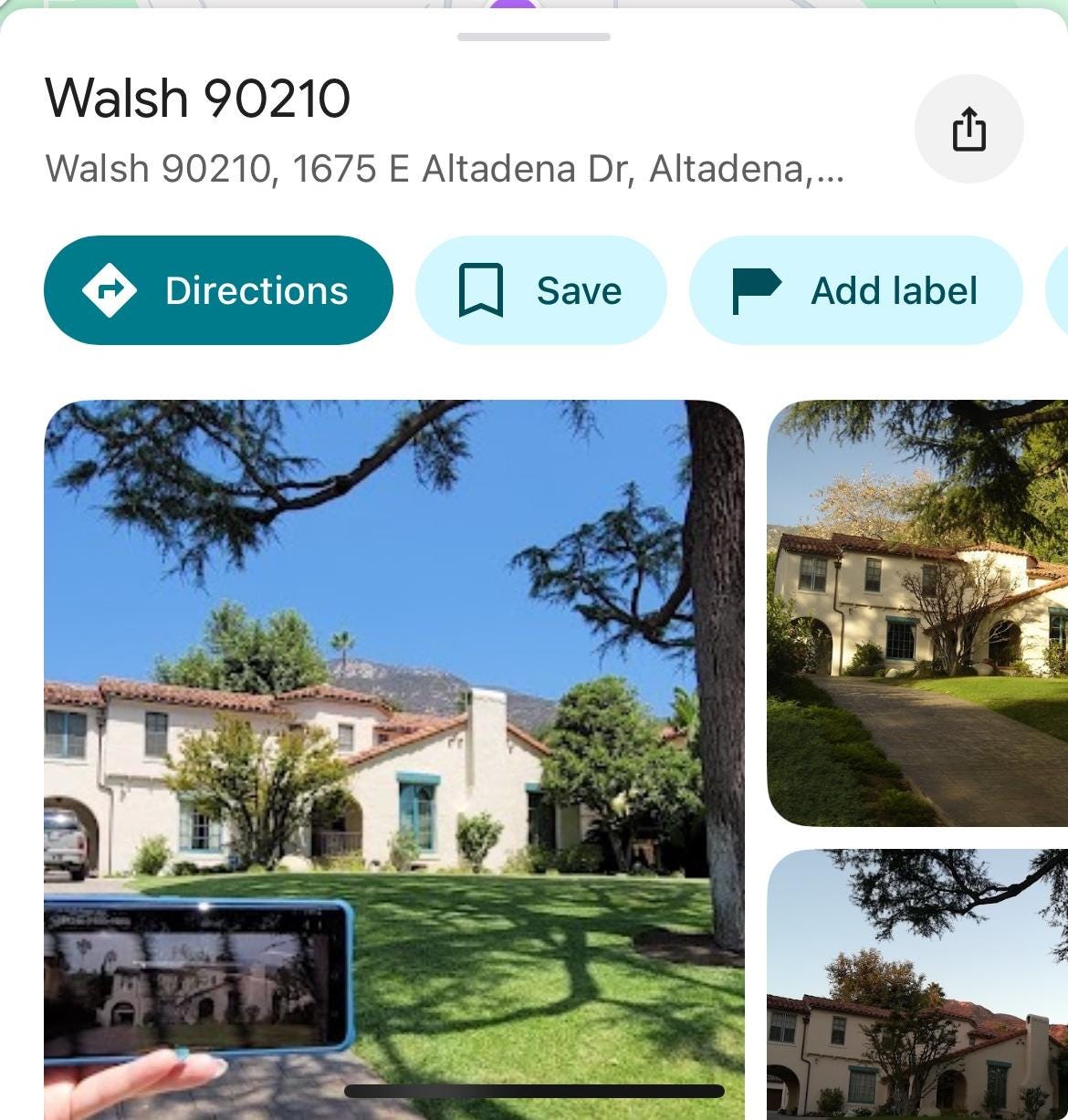

I’ve never been to Altadena. But I feel like I have. For a decade I watched it on Beverly Hills, 90210 with fanatical devotion as it stood in for the titular suburb. The homes of Brenda and Brandon Walsh and Dylan McKay are on East Altadena Drive.

My memories are on that street, too. So are my sister’s. So are America’s.

It was not supposed to burn. But it did.

I did not want to highlight trivial matters during a tragedy so until now, I told no one my thoughts — except my sister. Together we scoured the internet for updates, refreshing fire maps and parsing videos posted by fellow stealth 90210 sleuths. But now that The Hollywood Reporter devoted a full article to how Casa Walsh survived (no word yet on Dylan’s domicile), I feel I can discuss it.

Let me be clear: our foremost concern is the toll of the fire on actual Californians and their actual homes and communities. We are no strangers to climate catastrophe. My sister spent February 2021 gathering snow to convert into water during a record Texas freeze that knocked out utilities and killed hundreds of people. In July 2022, my Missouri neighborhood was hit by record rainfall causing a once-in-a-millennium flood that made my street look like this:

Photo taken by me outside my house, July 26, 2022

When a climate catastrophe strikes, you do not recover, even if you are among the spared. Some of my neighbors lost everything and I’m all too aware that it could have been me — and might be next time. To this day, when heavy rain falls, I start to shake and don’t stop until the rain does.

My heart goes out to L.A. The fires surpass any climate crisis I’ve experienced, and their ferocity is terrifying. For millions of southern Californians, a lifetime of memories disappeared in days. That is something with which people all over America should be able to empathize, given the prevalence of climate disasters.

But the strange thing about California, for us outsiders, is that we share some memories with you — in a way that should be abstract, but doesn’t feel it. To watch Los Angeles burn feels like losing America’s collective consciousness. It’s the destruction of childhood escape, the annihilation of fake places remembered more vividly than real ones. It is grief by association.

That this devastation arrives as the film and television industries crumble, fragmented by streaming platforms and corporate assaults on human creativity, makes the feeling harder to process. I’m grieving invented places and the real people who make them. I’m grieving future fictional worlds that may never be born and the manmade circumstances that birthed a cinematic inferno.

I’m contemplating the way AI and environmental devastation meet to assault our humanity. How they conspire to sell the lie that people and neighborhoods are replaceable by virtual doppelgangers, when they absolutely are not.

People cried when Notre Dame burned because they felt it belonged to the world. It was not merely an architectural marvel, but a record of pilgrimage and history. The pop culture landmarks of Los Angeles will prompt similar sorrow in those of a certain age. Our reaction might seem inane, but it comes from the heart. When a place is beamed into your home every week, it starts to feel like your own.

Especially in the 20th century, when to be recognizable was rare.

I tried to explain to my children what it was like to travel before the internet, when photographs of most places were not easily accessible, if they were accessible at all. You did not know what you would see until you arrived — which made it novel and surreal to see New York City, full of famous sights, or to fantasize about visiting LA.

When I finally made it there in 2018, Nakatomi Plaza and the Michael Myers House from Halloween were my first stops. I was bursting with excitement, greeting these sites of fictional slaughter like old friends.

I don’t know if that collective attachment exists for younger generations, who grew up able to see the world on Google Street View. But for older generations there are places that feel like they’re ours, even if we have never been there. They feel quintessentially American even if they exist only in L.A. If Casa Walsh burned, my sister and I would shed real tears. We would remember watching Beverly Hills, 90210 together with new sadness, because those simpler times would be gone with a finality too hard to bear.

We know those days are over — they left long ago, along with the illusory safety of the 1990s. But until recently, the Walsh House looked the same, a refuge of adobe and palms in a country spinning out of control. Someday we’ll visit, I would think and laugh at our decades-long devotion to this show. My sister and I don’t have much in common, but we always had Beverly Hills, 90210.

People rag on television, but it holds whole relationships together. Sometimes I worry it’s what holds countries together too.

The Walsh House still stands. Around it is an apocalypse of private pain and loss. Now I grieve Altadena, another place I’ve seen only through a screen, its unique history and sites explained on social media by its mourning residents. I grieve the real Pacific Palisades too. I wish the insulting stereotypes about wealth and race deployed to weaponize the agony of Californians would cease.

It's California today, it was North Carolina in September, and it could be anywhere next. Climate catastrophe is the new unified American experience, the one that replaced collective pop culture. The one in which ordinary Americans have been involuntarily cast.

The one watched on screens by a mass audience — an audience that sometimes acts like they’re not watching real people lose everything they love.

It is terrifying to think that catastrophes are what Americans have most in common now, but it needs to be acknowledged if we want to help each other survive. It is clear that powerful people do not want us to do so.

They want us to move on: from Puerto Rico and Florida hurricanes, from Maui fires, from North Carolina floods, from countless other climate catastrophes that provide opportunities for plutocrats to scoop up property at cheaper prices.

They want us to move on and move away.

I live in the inverse of L.A. My city rotted until it became appealing to Hollywood as the backdrop of post-apocalyptic thrillers. In 1980, John Carpenter chose to film Escape From New York in the St. Louis region because it was so rundown, he didn’t need to build a set.

The Chain of Rocks bridge that was the film’s grim “69th Street Bridge” has since been rehabilitated to its Route 66-era glory. Now it is a scenic Mississippi River hiking path over which bald eagles soar. It had a real-life comeback from a cinematic apocalypse.

I keep thinking about Chain of Rocks because I want the same positive outcome for Los Angeles. I fear its regional beauty will be lost when they rebuild. I want the California with style and character, the California where some fantasies are true.

The fires rage as I write. I’m still mourning places I’ve never been. I’m glad some were preserved on film, and hope I do not come to mourn that, too, as AI moves to replace the human experience. Humanity is under assault from so many angles, it is hard to process. It would be too much for fictional L.A. and real L.A. to go under at once.

But there is still individual memory, untouchable. California always felt most alive in dreams. I wish dreams were enough.

* * *

Thank you for reading! I would never paywall in times of peril. But if you’d like to keep this newsletter going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. That ensures every article remains open to everyone. I appreciate your support!

Casa Walsh on Google Maps.

View of the Mississippi River from Chain of Rocks Bridge. Snake Plissken approves.

I live in Winnipeg and it is not that cold here. Let that sink in. I feel for everyone in dire straits and newly unhomed, from Pacific Palisades to Gaza. Try to make positive change wherever you can is all I can say.

I have been wondering why these fires hit me so hard - so much harder than other catastrophes. You’ve explained it. It’s the familiarity of LA. Not just because I lived in Sacramento, not because my dad lived in Glendale, nor because I have kids in San Diego. It’s the prevalence of all things Southern California in our collective conscious. The hub of our collective consciousness has been destroyed, the place we look to for explanations and escape.