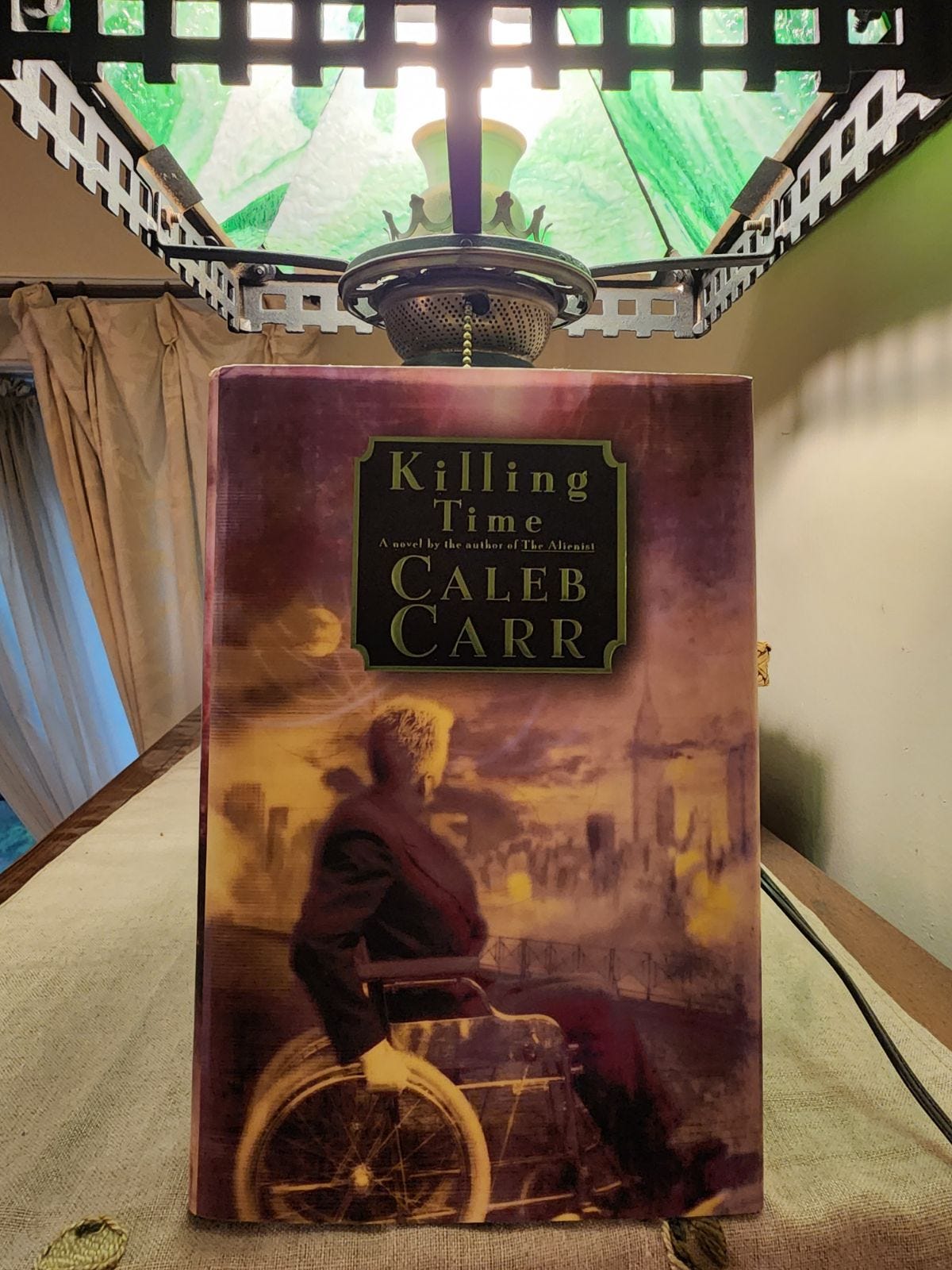

I am reading Killing Time, a book by historian Caleb Carr.

From the vantage point of 2023, it rehashes the terrible events of the 21st century: the war in Afghanistan, the global pandemic, the 2007 financial crash. It describes our dire present: a fascist revival in parts of Europe, a war-torn mafia-state Russia, an Israel overrun with fanatics, environmental devastation everywhere. The most reliable global export is pain.

Above all, it mourns the internet. What began as a revolutionary exchange of free information has dissolved into a cesspool of propaganda, nonsense, and AI illusions designed by plutocrats with brutal motives. By 2023, the internet has become so unusable that it’s hard to even tell if someone is dead or alive. History is being lost or rewritten, and citizens are cajoled into violence by online manipulation of their real and perceived traumas.

None of this should be revelatory. Except Killing Time was published in 2000, and Caleb Carr is dead.

Carr died of cancer in his home, a property named Misery Mountain, in May 2024: one year into a dystopia that used to exist only in his mind.

Carr was known as a tortured soul. The son of Beat writer and convicted killer Lucien Carr, he endured an abusive childhood among a debauched intelligentsia. He shunned his father but followed his profession. His first published work was a letter he wrote at age 19 to the New York Times bashing Henry Kissinger.

His non-fiction books on military strategy interested Bush administration officials after 9/11, until he proclaimed that any state that waged war on civilians was a terrorist state destined to lose — including the United States and Israel.

Carr died a recluse. His final book was a non-fiction tribute to his best friend, his cat.

Killing Time is a work of fiction that managed to predict many major events of the 21st century. The novel, set in 2023, is barely mentioned in his obituaries. People don’t like this book, and in 2000, they were angry at Carr for writing it.

My heart is with Carr. It’s a terrible feeling to know too much, too soon.

* * *

I was 21 at the dawn of the 21st century. I can close my eyes and let the era fill me: that optimist arc dissipating fast as a rainbow. A century of promises hovering like clouds, only to break and pour like a torrent of tears. The demarcation line between centuries still feels like something you would stab someone with.

After I heard about Carr’s death, I dusted off my hardcover of Killing Time, and started reading it again.

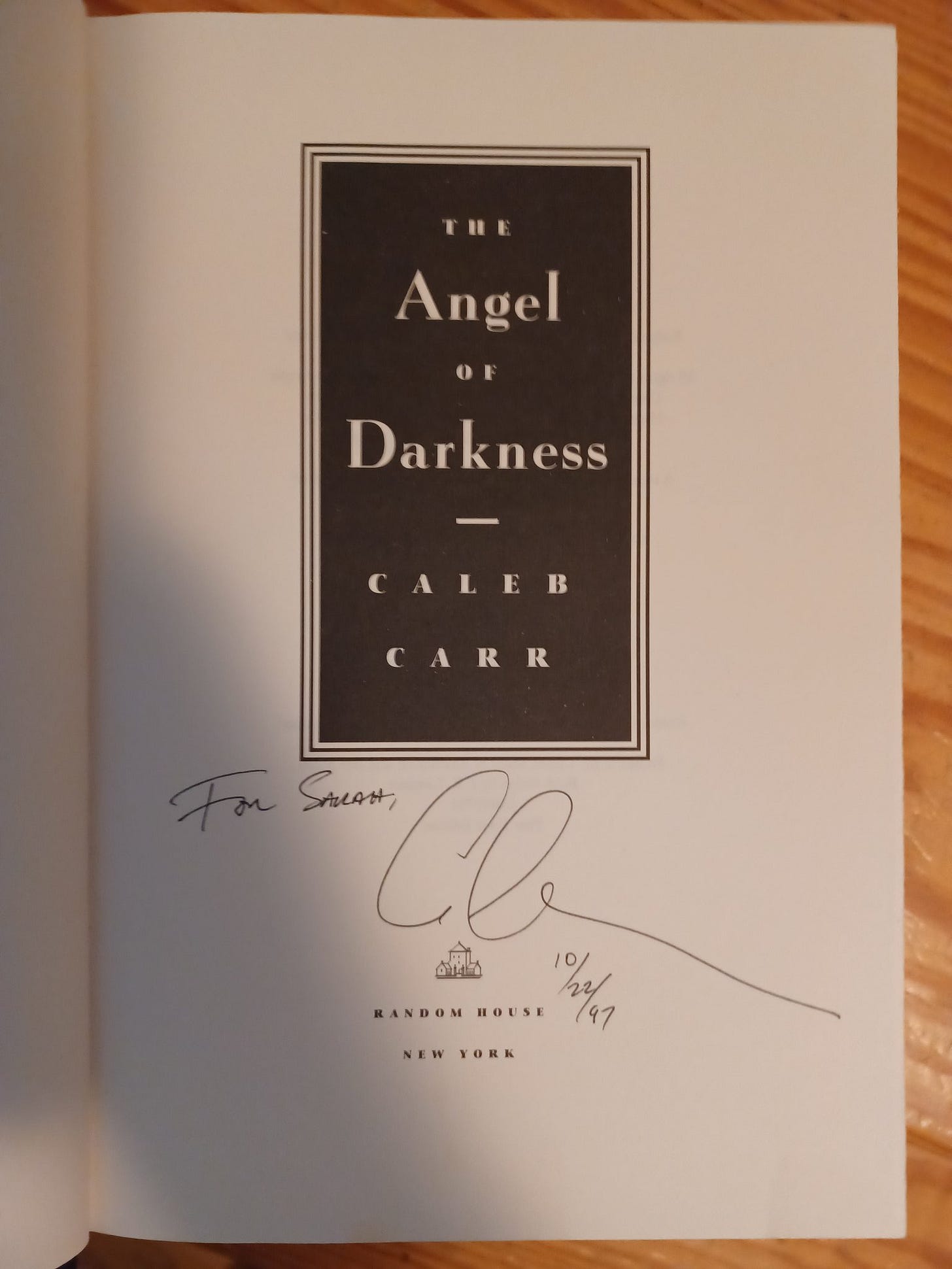

In 2000, Killing Time was panned. Carr, a military historian acclaimed for his best-selling novels The Alienist and its sequel, The Angel of Darkness, had turned to dystopian science fiction at a time when the world was declaring the internet an inherently democratizing force.

Reviewers derided Carr as a doomsayer. They wanted his dark crime fables to stay in the turn of the 20th century, and not twist the turn of the 21st. In 2000, history was supposed to have ended, in a happy way. Not in the Caleb Carr way: fungible, illusory, cruel.

I was rereading Killing Time the day that Noam Chomsky maybe died. As I write this, I still don’t know if Chomsky is dead or alive. No one can seem to verify it. The attention economy is so black market, you can’t even manufacture consent.

This is how Killing Time opens: a killer leaves DNA behind, an analyst laughingly says he has found the culprit unless he has a twin brother, and the narrator responds that he in fact does. The twin brother was famous, but the internet had become so enshittified that rudimentary information could no longer be found.

“The sum total of human knowledge is supposed to be on the damned Internet — you mean they missed something as basic as that?” the narrator says in disbelief.

I check Twitter to see if Chomsky’s dead. He’s in limbo, trending. Baphomet is, too, for some reason. I get off that shitshow and back to Killing Time.

The novel is not Carr’s best work. The characters feel like vehicles for prophecy; the plot an excuse to reveal real plots of the near future. It’s the rare book where the exposition is more interesting than the action.

When I read it in 2000, I was overwhelmed by what seemed like odd side details — a war in Afghanistan, versus the war in Afghanistan, which had not yet happened. Details that seemed implausible in 2000 — in Killing Time’s pandemic, overwhelmed hospitals abandon basic safety standards and resources grow as scarce as empathy — now seem like simple and terrible facts.

Carr’s characters recite a motto: “Mundus vult decipi”, Latin for “The world wants to be deceived”. It is reminiscent of the old Mossad motto — “By way of deception, we shall make war” — and also a fairly accurate summation of 21st century affairs. The evil characters tend to say it most, along with frustrated characters trying to comprehend the evil.

It’s hard to argue with the truth of it. If the world hadn’t wanted to be deceived, it would have heeded Carr’s warnings about the internet in the first place.

* * *

I am about to go away for two weeks. I’ll be back July 1, and I hope you don’t hear from me. I’m trying to clear my head. Over the last year, I wrote one book, forty articles, and three eulogies. More death is coming soon.

Grief requires space. I need real land, real people, real words, to process real loss.

I’m going to bring Carr’s novels with me and read them on the road. They are good stories, and their confrontation with evil is reassuring in an era when so many rationalize cruelty and violence away.

Ironically, his dark books bring back memories of happier times — the time before I lived in the future Caleb Carr saw coming. The time I met Caleb Carr.

In 1997, I went to New York City to see Carr read from his new book, The Angel of Darkness. I arrived at the bookstore very early, because I was a teenager and nervous. I think I know what bookstore it was, but I’m not going to name it, because they were assholes to me, and if I get it wrong, I’ll feel bad.

“There’s not going to be room for you,” the proprietor said when I sat down in a row of empty chairs. “We all know each other. It’s that kind of place. Maybe you can stand near the exit sign.”

“What do you mean?” I asked. I was the first person there. “I’m here for the reading. I saw an ad in a magazine. I took a lot of trains. I don’t understand?”

“Why don’t you go back—” she started, and then Caleb Carr appeared.

“She can stay where she is,” he said, nodding at me, and darted away. The owner glared at me and left me alone.

I spent the evening confused by the altercation, excited to see Carr in person, eager to read his new book. I felt good about the future. The world was so open I could meet a writer I admired, even though a jerk tried to prevent it. What else awaited me?

After the reading, Carr asked my name, smiled, and signed my book. I remember talking to him a little, but I can’t remember what about. I wish I’d written it down.

I’m now around the same age Caleb Carr was at that signing, living in the dystopia he envisioned. He was kind to me, and I always remembered that. I remember it every time I sign my own books for my own readers.

I didn’t know about his struggles. But I’m glad he stuck around. He knew enough about the world to mourn the future more than the past, and he kept on writing anyway.

Thank you for reading. This newsletter is made possible by volunteer paying subscribers. If you like my writing, please consider a paid subscription — it’s how I pay my bills and keep my work free and accessible to everyone.

“He was kind to me, and I always remembered that. I remember it every time I sign my own books for my own readers.”

I hope vacation provides you the same refreshing sentiment.

For a deeper understanding of Carr’s beautiful mind and heart, I recommend his recently published memoir, My Beloved Monster, Masha, the Half-Wild Rescue Cat Who Rescued Me. Even if you don’t like cats, this book delves into his life and philosophy in profound, poetic ways, a moving and intelligent memoir.