In 2023, Twitter crumbled like an empire, its X-iles shuffling off to their own corrupt kingdoms. They went to BlueSky, Threads, Mastodon, and other social media networks, where they spent most of their time bitching about Twitter.

I am still on Twitter. Even if I were not, I would keep my account, because it is a chapter in an archive of humanity. That is one reason Elon Musk is manipulating and murdering the site. An archive of history -- in particular a time-stamped chronology of state corruption -- has power beyond what money can buy.

Chronology is the enemy of autocracy. Twitter shows who knew what and when, and gives some insight into why. Twitter is where dissidents organized and politicians confessed their crimes. To alter Twitter is to alter history, and that is the appeal to autocratic minds. Voices can be silenced, witnesses disappeared, and history rewritten.

“If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it,” wrote Zora Neale Hurston, an underemployed anthropologist and muckraking journalist who received only belated recognition for her searing, scathing, idiomatic prose.

In the 21st century, you can be loud about your pain. You can weep to millions of witnesses. And then tech lords can kill you and replace you with a digital doppelganger who declares that yes, you did enjoy your pain, and what’s more, you deserved it.

There is no clear way to win in the future when oligarchs can purchase the past. But surrender is a sure way to lose. My words are on Twitter and I stay to guard them.

But I am only human – so far – and as a human, I needed a break. I am older than Danny Glover when he was too old for this shit, and I want to keep This Shit from seeping into my soul.

This Shit is the sediment of social media. Memes instead of memory, repetition instead of reflection, slogans instead of sentiment. You cannot build anything in there except cults. If you don’t watch yourself, the cults build you.

The rot got there before the robots did. Artificial intelligence was the culmination of social corrosion that made it hard to tell a person from a machine -- not because the bots were so realistic, but because the people were so fake.

I was told to fear AI, and I did, since it ate one of my books, The View From Flyover Country, without my permission, and was digesting it back out as This Shit.

In 2023, I felt the inverse of inspiration. I wanted to write something so superficial that AI could only scrape its skin. But instead, I went silent. A Harlan Ellison story kept echoing through my mind: “I Have No Mouth, And I Must Scream.”

I hit the virtual road, but not for a social media network: I went to Duolingo. One hundred and seventy-two days later, I’m still there. You can tell, because I recite my streak like a prizefighter who no one informed is a shadow boxer. Turned out the quantitative dopamine of Esta Mierda got in me after all.

Que pena, but at least I know when I’m talking to robots now.

* * *

My Duolingo addiction began with Breaking Bad Camp. This was something I invented in the summer of 2023 for my twelve-year-old son, who had two goals: to watch Breaking Bad, which I had forbade, and to avoid any organized activity involving other middle schoolers, for which I could not really blame him.

“You need to do something,” I told him. “You can’t just sit around. You should be, like, learning shit.”

“I can do something. I can watch Breaking Bad!”

“You’re too young.”

“But you let me watch [redacted].”

“That was during the pandemic. Or the part of the pandemic where they admitted there was a pandemic, and all the parents stayed home to watch inappropriate television with their children.”

“What if you watch with me, like when you let me watch The Shining when I was seven, and you just flipped over your iPad during the gory parts?”

This is true. As a result, my son had watched a version of The Shining about twenty minutes long.

“What if,” I said, “we watch Breaking Bad together. Only after every episode, you’ll write a report on what you learned. You’ll learn chemistry. And social studies! And you’ll do thirty minutes of Spanish on Duolingo every day. Let’s have as a goal that by the end of the summer, you’ll be able to understand the cartel without subtitles. Those are the rules of Breaking Bad Camp.”

My son stared at me like Walter White staking out Los Pollos Hermanos.

“You’re serious? I can watch Breaking Bad?”

“You’re not ‘watching Breaking Bad’. You’re going to Breaking Bad Camp with me, the head counselor. You are having an educational experience.”

“Mama loca,” my son laughed. Then he said, “That means, ‘I love you, Mommy, thank you for not making me go to real camp!’”

And so began Breaking Bad Camp. We would watch one episode a day, unless it was a really good season, in which case we’d have to get another hit and watch two or three, but it’s a show about meth so what do you expect.

My son produced quality reports like the following:

Breaking Bad Camp came with English homework. We read episode reviews, all of which now seem like they were written by literary geniuses. The degraded quality of online writing is never so apparent than when revisiting the blogs of the 2000s. The proper sourcing and well-structured prose. The startling realization that these careful and thorough works were considered lowly compared to print. The Golden Age of Television ended in mournful outrage, but the golden age of online television reviews had departed quietly, and I missed it.

“This is what life was like when you were born,” I told my son. “Before the memes.”

“The 2000s: no to memes, yes to meth,” my son said, and made a note.

The only obstacle to Breaking Bad Camp is that I could not evaluate my son’s Spanish. I have studied eight languages, but only learned one well (Uzbek) and a couple proficiently (Russian and German). I like learning languages for the joy of it – deciphering the alphabets and decoding the grammar and letting the rhythm of the language reorient your mind once you understand enough to hear it. Automated translation could never replicate this experience.

But I had never learned Spanish, except for profanities on the school bus and toddler vocabulary on Dora the Explorer. I was curious, especially after a summer of Salamancas and the quasi-espanol of amigo del cartel Saul Goodman.

“You should join Duolingo,” my son said. “We can do a Friends Quest.”

A Friends Quest sounded good. I was low on friends and my real-life quests tended to uncover atrocities. I needed to destroy my brain and rebuild it in a new form. I wanted to say pretty words like mariposa and put adjectives after nouns, a thrill cheap.

I let my son pick out my screen name, which, since he is twelve, is a dirty joke Bart told Moe on The Simpsons.

In the time I used to spend on Twitter, I started studying Spanish. I played Duolingo in the morning to get my coveted bonus points. I played in the middle of the night when I woke up crying from nightmares. I played while government lies kept coming about covid and climate and coups, and I watched Spanish-speaking cartoon characters discuss gripe y cambio climatico y derechos humanos.

I obsessively played a timed vocabulary game, Match Madness, during trips to visit a dying relative, because I like racing a ticking clock and actually winning. One thing I had not considered before Breaking Bad Camp is that it’s possibly not the best plan to watch a show premised on lung cancer while someone you love is dying of lung cancer. Like Jesse Pinkman, I have a long hard record of vulnerable mistakes.

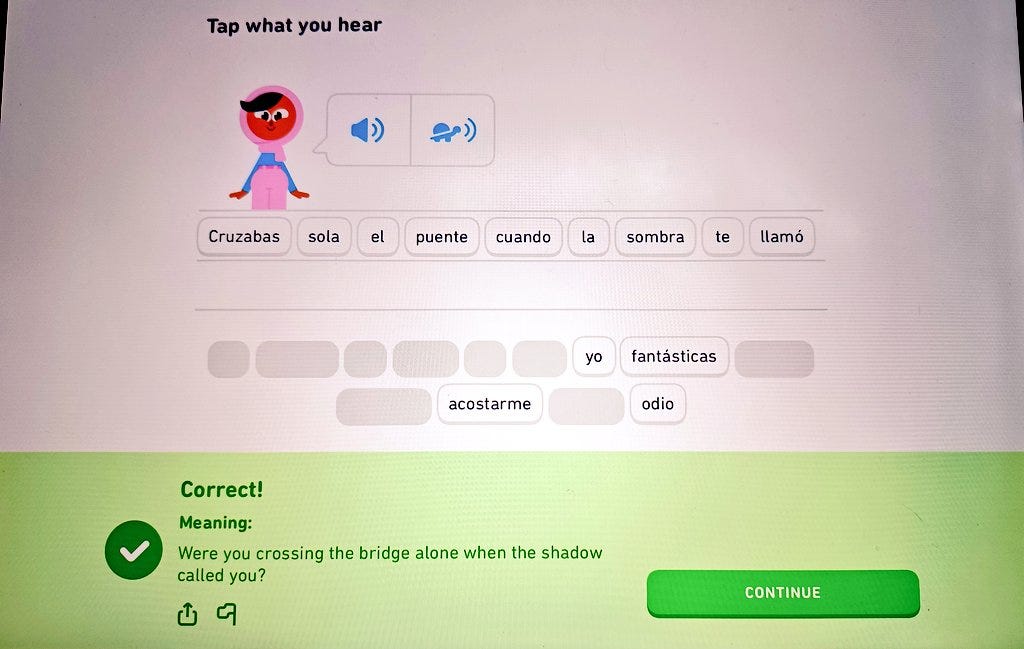

In the summer of 2023, I blocked out the pain in my heart and horror of the news and doubled down on Duolingo. It soothed me with sentences that captured my mental state, like “Cruzabas sola el puente cuando la sombra te llamo?”

Why yes, I was crossing the bridge alone when the shadow called me.

* * *

With the exception of German, most of the languages I have studied bear little resemblance to English. In graduate school, I studied Uzbek, and spent a lot of time translating Uzbek poetry. This was before Google Translate, and took forever, but poetry is impossible to capture through a machine anyway.

Most of the poets I translated were dissidents from Uzbekistan who had left after their government slaughtered roughly 800 protesters in the city of Andijon in 2005. They went online to document the massacre, which the government denied committing, and to express their anguish and anger. The main way they did this was through poems, a tradition that dates back centuries in Uzbekistan, and remains common today.

Every country expresses its true heart in poetry, including America, where we just call the poems songs and label them country or rap or pop. The words that Uzbek poets used to convey their political plight often had Persian or Arabic roots: adolat (justice), ozodlik (freedom), vatan (homeland), zolim (tyrant). They rejected Russian loan words, including the favorite of foreigners.

“We don’t like ‘democracy’,” one poet told me. “The word, not the idea.”

Demokratiya had become cheap and cruel: a buzzword the government sells with a sneer as the mafia state shakes you down; a lure NGOs peddle as they promise to solve your problems without hearing what they are. Demokratiya was a sign that someone did not have your back unless they were painting a target on it. The word is still viewed that way in many states of the former Soviet Union that proclaimed themselves “democracies” while remaining dictatorships.

In Uzbekistan, demokratiya had no real relationship to one of the most important words: xalq, “the people”. Uzbeks never had a system of government that empowered the people. But people who have never experienced freedom value it all the same.

Sometimes a Western government will proclaim that a country “is not ready for democracy” due to its history of tyranny. But that’s usually an indication the West is about to go in and drain resources before propping up a puppet when the country is deemed “ready”. This, and not some innate revulsion to liberty, is why many remain wary of the foreign loan word “democracy”.

* * *

When I was in college, I studied Ancient Greek for one year, a consequence of reading too much Donna Tartt in high school. While seemingly impractical, studying Ancient Greek was a solid move for someone who writes in English. I started breaking down words into parts I recognized from ancient roots, especially in politics, where kratos – power, or rule – would appear. Autocracy: rule by one man. Kleptocracy: rule by thieves.

Democracy: rule by the people.

Whenever I hear Americans proclaim that democracy is either dead or eternal (it is often the same politicians speaking in extremes, usually while they are asking you for money), I return to the root: the power of the people.

I do not instinctively reject the word “democracy” because it was not imposed on me by a foreign country. It is the power to which I am entitled but never received. Democracy was never fully realized in the United States and has been stripped away even more over my lifetime.

But I feel the word in my soul in a way that is natural – the way you feel a poem.

Americans have lost much of our representative democracy through Citizens United and the 2013 partial repeal of the Voting Rights Act. But we have not yet lost freedom of speech or freedom of assembly – even though they are under heavy attack. These are our most powerful rights, because they come directly from the people, without the intermediary of officials. They express and protect our will.

The rich, vast word of “democracy” should not be reduced to “elections” — both because there are so many crucial rights we could still lose, but also because elections will not protect those rights when elected officials refuse to honor the law.

I believe in democracy: the power of the people. The US government believes in democracy too. But they do not believe that all of us are people.

They leave out that part when they take their little oaths.

* * *

Breaking Bad Camp ended in August. My son went back to school, and due to a nationwide shortage of Spanish teachers, switched to Latin. He loves Latin like I loved Ancient Greek: the way it lets you pull the scaffolding off the architecture of English and let the roots lie exposed.

I returned to Twitter in September but continued with Spanish anyway. It’s the easiest language I’ve learned, my first Romance language, relaxing like a puzzle and alluringly familiar. Sometimes I’ll be studying vocabulary and memories of heavily Latino cities I’ve visited in the US – San Antonio, Santa Fe, El Paso – enter my mind, and I want to return and see them in the light of my new language. Spanish is America’s heritage as much as English.

I am still a novice in Spanish, a “low-intermediate” reader. I am ignorant enough to stay curious. I get fixated on words that resemble English ones but carry meanings different enough to be illuminating, sometimes almost subversive. My current obsession is equivocado. I assumed it meant “to equivocate” – to prevaricate, to lack conviction and clarity.

But in Spanish, it simply means wrong. “Me equivoque” means “I made a mistake” or “I was wrong”. There are no two ways about it. That belief that there are two ways, is, in fact, why you are wrong, according to the etymology explained on this blog, which I rely on because my Spanish is not good enough to figure out the etymology of anything on my own. Equivocado derives from Latin meaning “to call in two different directions”, with the result that you lead yourself astray. And it’s your own damn fault.

That is the word I needed to describe the horror show of the US government as it supports a genocide in Gaza while issuing statements lightly condemning the very violence that they are funding.

They are equivocating, and they are also equivocado. They are wrong for equivocating, wrong beyond wrong. They are evil for equivocating as the corpses of children pile up. Their excuses are a slap in a dead man’s face. There are so many layers of wrong that I need two languages to express them.

On December 6, Israel killed Palestinian writer Refaat Alareer in what appears to be a targeted assassination. Alareer was a poet who I had followed on Twitter, and whose English-language articles I had read over the last decade. Like many who followed him, I grieved his death even though I did not know him. His life and works remind me of Uzbek poets I knew, many of whom were imprisoned or killed by the state for baseless reasons.

Dictatorships murder poets because poets convey the feeling of a people. They heed Zora Neale Hurston’s warning to document your pain. They are the ultimate witnesses, and as such, are priority targets.

I have so much to say but I am often out of words these days. I write because if I don’t, they may say I enjoyed this time.

I like to listen to music when I’m writing. Lately I listen to Roy Orbison, and I think about how my dad said his voice is “like water” and how you don’t need to know English to understand that. Music is universal, like poems, and like tears.

And I listen to “Llorando”, the Spanish cover of Orbison’s “Crying” by Rebekah del Rio, because now I can understand the lyrics. I always understood the pain.

* Lo siento if I botched any Spanish in this article, I am still new at this!

** If you liked this article, please consider subscribing! Paid subscriptions are the only way I can keep this newsletter going. Thank you!

I have the attention span of a toddler these days, but I read every word you write. You are my righteous rage idol ❤️

In this time of chaos, madness, and uncertainty, you’re a constant. Your ability to put what you’re feeling, seeing, and thinking into words that can be understood and reflected on by all reads them is phenomenal. You’re one of the very best at what you do, and we’re all better for it. Thank you as always.

P.S. I’m on Day 771 of Duolingo French.