I spent Sunday morning on a river without a current.

We arrived at the put-in on an old school bus roaring down Missouri dirt roads at breakneck speed. I stuck my head out the window like a dog, disregarding the danger, craving the breeze.

We’d driven two hours south to get away from everything. I do this enough that some suggest I should just move. But then the thrill of escape would be gone.

I needed an escape from waiting. Waiting for what, I don’t know, only that it will be something bad.

We don’t know what will happen in November. We just know it will be epoch-shifting — unless it’s more of the same. It will kill us in silence — unless it screams with murderous intent. It will shock but not surprise — because we have lived inside a rerun for eight years. A rerun like zombie roadkill, a rerun like a sequel to a remake of a show that should have never aired.

We live in suspended animation. Too bored to be terrified, and too terrified to be bored.

There is a high level of bullshit involved in proclaiming “this election may be your last” every four years and then doing little but fundraising off fear. But that doesn’t change that the GOP threats that the Democrats describe are real. I’ve faced them since my Reagan-era childhood, and watched Democrats defer to them since then, too.

It also doesn’t change that a remarkably bipartisan lack of concern over protecting Americans from sedition, pandemics, climate change, genocide, and other existential threats leaves me suspicious that the election is less of a game-changer than the next stage of a plan.

I waited for the river to lift me up and propel me, but it never did. The day was hot and humid, and my husband and I and children paddled hard, forcing the raft along. I had just had surgery and should not have been doing this, but I insisted.

The other thing about time running out is how desperately you cling to the days before the fall.

In my attempt to Do Everything Before It Ends, I decided to float every river in Missouri. I’m nine rivers into this plan. I’m glad I floated the Black River, even though it hurt like hell. At multiple points, the river ran so low it turned to rock, and we disembarked and dragged the raft. Pebbles burnt my feet like shards of fallen sun.

The water would rise and return, and I would rejoice, but I knew relief was fleeting. We were alone in a beautiful land: crystal water, forested cliffs, bass and sturgeon swimming low and free. Sometimes the river was so deep it turned cobalt. The Caribbean of the Missouri, but no beat, no banjo and no blues, just stillness and sludge. The sun beat me like a fist, tormenting me with dead futures.

The dread and the dredge, I thought, is that all what’s left for me?

I knew it wasn’t true. But I felt it, and sometimes feelings matter more.

* * *

“I can’t write,” I told my husband days later.

I was stuck. I didn’t know why. It felt like the world had shifted while we were on the river, or maybe it was the algorithm, or maybe the algorithm was the world, and that was the real problem. But even that was wrong.

My writing wouldn’t move because my thoughts wouldn’t move. They were stuck in suspended animation. They were locked in timelessness, which is worse than being locked in time.

Time you can examine. That is why dictators want to destroy history, so that you’ll never understand your place in it. Today the first draft of history — journalism — is being destroyed. It has been replaced with influencers and robots, stripping human beings of our sense of time. You can’t remark on what you do not know is happening. You can’t plan around it either.

My husband reminded me that I had just had surgery, and that I spent the weeks before the surgery wondering if I had cancer, and then another week waiting for biopsy results, which of course alters your sense of time. (It was benign; I’m fine.) That potential threat was enhanced by the terminal cancer of a close relative, and the wrenching wait for news that has accompanied every day since that diagnosis.

I hate the waiting, and I dread the day the waiting ends.

Then there are the prosaic waits: the wait for what will happen after my daughter graduates high school in 2025 into God knows what kind of America; the wait for my new book that will be released in that same frightening spring.

These should be points of family pride. But the anticipation is obliterated by existential threats beyond my control: the unpredictability of elections and unpunished coups and mutating pandemics and climate change. The waiting that repeats or worsens but never stops.

The wait for Trump to disappear. Biden did. It can happen.

The shock of Biden’s departure from the race spurred elation less over its result — the candidacy of Kamala Harris — than the thrill that sudden, enormous, positive change could happen in America. Regardless how one feels about Harris now, people remember fondly the free-form velocity of those days.

Would that they return, instead of making us feel like we are in one of those beautiful old homes that a developer guts and paints grey, offending everyone in their quest to offend no one.

* * *

Americans are waiting for the 2024 election to end. We are waiting for a culmination so we can move once more.

But what this era may culminate in frightens me. The rise of accelerationists — usually profiteers cloaked as burn-it-down revolutionaries — is one source of worry. I understand how accelerationism appeals to people rightly appalled by this political climate. But I’ve seen enough things burn to the ground to know they don’t build back better; they pave over your grave.

I look at Gaza and the casual bipartisan cheer at its annihilation, and I shiver.

My response to encroaching autocracy has been to pretend that I’m free. Write and say what I think, criticize authority, disregard death threats, stay weird (even when the Democrats seem keen on outlawing it). But it is easier to prepare for the worst when you are dealing with a predictable, plan-blurting proto-autocrat, like Trump, than with the more nebulous warmongering networks of mandated joy and broken promises that followed in his wake. There is no clear way to fight that.

They call this feeling demoralization. But my morals are doing fine. It’s the opportunity to apply them that is waning.

* * *

There is a scene on Curb Your Enthusiasm where Larry David, stuck on a shortcut gone awry, announces, “I can’t sit in traffic — I’m too smart!”

I think of this quote whenever someone treats this pantomime of an election — one in which a career criminal seditionist is a main candidate and we are supposed to “beat him at the ballot box” and then return to inertia with a dash of genocide, unless coups and rigged courts intervene — as an expression of the people’s will.

I’ve done my part. I am a Good Voter. In August I voted for Cori Bush, my lawfully elected representative who Democrats and Republicans and AIPAC conspired to destroy. Bush had condemned the slaughter of Palestinian civilians, and deep pocket donors decided she must be removed.

Now my city, St. Louis, has no representation in Congress. The Democrat who replaced Bush, Wesley Bell, is beholden to the foreign state lobbyists who fund him.

I’m too smart to sit in that traffic.

The crisis of November is that there is little sense that we can change our fate, but a strong sense that our country’s fate will dramatically change anyway. Our focus will then turn to survival, but we don’t know what we will be trying to survive.

It is hard to live this way, much less work.

As I tried to work, sleepless and sad, I became convinced why I no longer could write: the specimen the doctor had cut out of my body held my imagination! Sure, it had possibly been cancerous — but that was a ruse to test my resolve. Now it was gone, sitting in some biopsy container, and with it, my ability to think and dream and write.

My husband listened to my theory and gently assured me that the last thing I was lacking was imagination. The thing I was lacking was sleep.

* * *

I went to the river to float my problems away and found the only things flowing were the tears on my face.

I looked to the sky and thought of the astronauts who believed they would only be in space for eight days but are stuck until 2025.

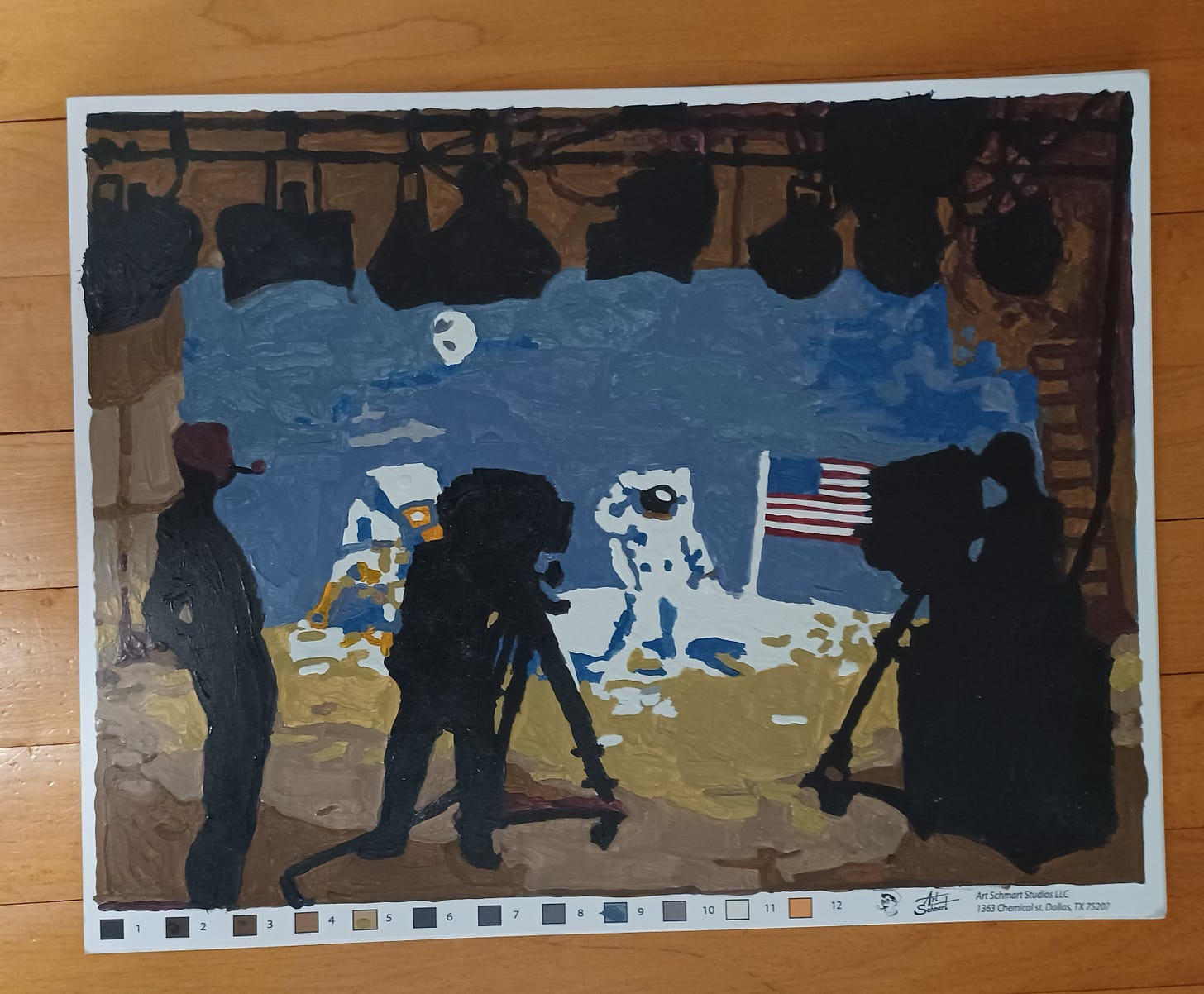

I thought of the global pandemic that the World Health Organization initially denied was serious, and how in 2020 when I was bored, I did a paint-by-numbers of the moon landing as conspiracy, a picture of shadowed men smoking pipes on a sound stage.

I thought about the artist on Etsy whose conspiracy paint-by-numbers shop went under once people “returned to normal”, and how when normal is not safe or kind but a liar’s terrain, I’d rather stay strange and even a little sad.

When I finally slept, I felt better. Not only because I had been so tired, but because I cried myself out. Tears can be a form of compassion. I’m not crying for myself, you know. I am the least of my problems.

These days I can’t even paddle downstream without a struggle. But I’d rather move with my pain and sorrow than confine myself to a fate contrived by fools. Or else suspended animation will slither back in, and I’ll blame myself, and then blur myself, until all feeling — good and bad — is gone.

I am happy I can write again, even if I’m rambling. That’s what rivers are for, rambling along: seeing the sights, the journey as destination.

Even when you have to dredge.

* * *

Thank you for reading! This newsletter is funded entirely by voluntary paying subscribers. That allows me to keep it open to everyone, and I don’t want to paywall articles in times of peril. This newsletter also pays the bills for me and my children. If you like what I do, please subscribe!

The Black River.

You know you want one.

This was really powerful. I'm almost always moved by your writing, but then every once in a while, the beauty of your prose really hits, and it's a powerful punch. Very glad to hear you're well, and thank you again for sharing pieces of yourself with us. Cheers, Sarah

You're not rambling....you're weaving! (I'm a Professor of Literature.)