I am in The Black Place.

The ground is white and cracked and leads to undulating gray hills. The hills stretch for miles, but I know which one I want. I spot it like my own reflection and start walking its way.

There are times I pass a mirror and don’t recognize myself. I got old too fast and saw too much. People think I’m younger than I am until they catch the look in my eye.

The Black Place has seen too much. It absorbed its dark recollections into the soil and put them on display. It is an honest mirror, reflecting the things a person is taught to hide, and making them seem beautiful again.

I walk to The Black Place while my husband and son stay in the air-conditioned car. My parched land novelty tour does not interest them. I tell them I’ll be back in ten minutes. When I return, it’s been an hour. Time loses all meaning in The Black Place.

The Black Place is off a service road in rural New Mexico. It is not marked and not obvious. It surrounds you gradually, like depression. The instinct of many travelers is to move on. I’d moved on before, and regretted it.

It is better to visit The Black Place than to have the black place visit you.

* * *

We left Cortez that morning for Navajo territory, stopping for breakfast at a frybread shack. The tiny turquoise restaurant was decorated with star-spangled tables and tributes to John F. Kennedy. We sat by a coal-burning stove and paid with exact change as required. Outside, horses wandered, kicking up dust on a dirt road. It could have been any year since 1964.

“Ask not what your country can do for you; Ask what you can do for your country,” said a plaque on the wall. That seemed too big a request for 2024. I could only think of the violence this country had inflicted on the Navajo people, and then on Kennedy, in the end. Maybe the sign was not as incongruous as it seemed.

We returned to the car and headed south. I don’t tend to revisit regions on road trips, but I make an exception for The Four Corners. In 2018, I took my children to the ancient dwellings of Mesa Verde. In 2023, we hiked Monument Valley. In 2024, we saw the 13th-century stone towers of Hovenweep and Aztec Ruins. We wandered through the Canyon of the Ancients, strewn with boulders shaped like giant skulls.

These sites are being threatened for destruction by the US government, but they always were. The threat is now more blatant, more flagrant, but the region long bore this burden. This land doesn’t fool you with false promises, nor does it bow down. There is no denial of the grandeur of what was and what might have been.

There is the stubborn persistence of what is.

In Cortez, I bought a Navajo rug. It has a seam on the border called a ch'ihónít'i, or spirit line. The spirit line protects the weaver from the emotions of the person who bought it. The artist wove herself an exit from her creation.

I look at my rug and am grateful the woman who wove this beauty is spared my thoughts. I feel longing for the West — and the lonesome embrace of The Black Place.

I want to go back, but that’s the American mantra. No matter the place, the time, the reason — everyone wants to go back, because the new forward is a void.

You can’t hold forward in your hands. Forward is looser than dust. When it comes to The Black Place or The Nowhere-Place, I choose The Black Place.

* * *

I’m reluctant to give directions to The Black Place since industrialists want to destroy it. We parked near a field of oil tankers and fracking equipment. The Black Place is on public land, so I wasn’t trespassing, but no boundary is marked between the corporate and the corporeal. Machines groaned behind me, sucking life out of the earth.

Between 1936 and 1949 — during the Great Depression and the birth of the atomic bomb in nearby Los Alamos — Georgia O’Keeffe drove 150 miles from her adopted hometown of Abiquiu to remote New Mexico badlands. She returned over and over, camping overnight, painting a dozen versions of the same place. When it got too hot, she crawled under her car for shade.

She called this landscape “The Far Away”, and later, in the titles of her paintings, “The Black Place.”

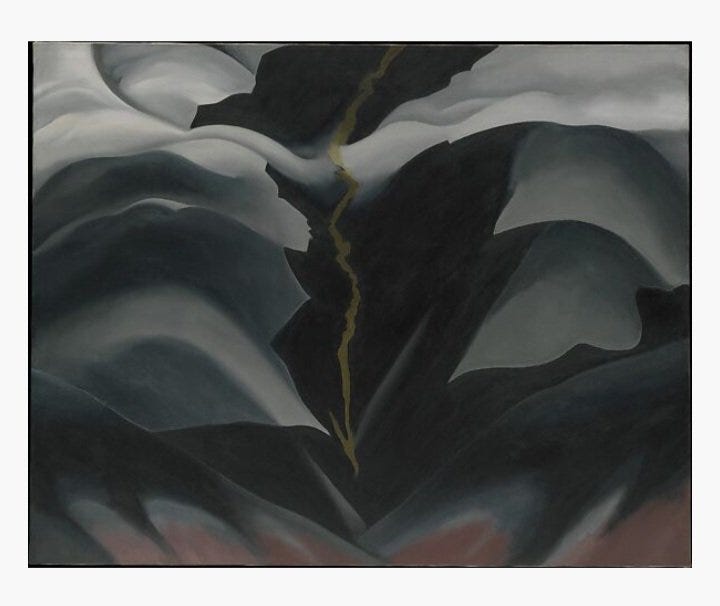

The most famous version of The Black Place shows black and grey rock cut through the center with a jagged olive-green streak. Flashes of white and red line the edges. Some find the fledgling greenery of The Black Place hopeful. What I find reassuring is the blackness, so strong I can recognize it from a painting eighty years old.

I wandered the badlands until I saw it, thinking this can’t be right, the keys of history do not unlock so easily. But they did. I knew The Black Place by sight, same as I know it from a painting, same as I know it from my soul. I knelt to get a photo. My husband took a photo of me, looking from a distance like a pilgrim at a shrine.

Realism was never O’Keeffe’s goal with The Black Place. The paintings are amalgamations of mixed feelings and foreboding themes, none particular, as relentless and resilient as the land portrayed. If you were to draw both depression and what it is like to survive depression, you might draw this.

Georgia O’Keeffe died in 1986. It doesn’t seem possible that my life and hers overlapped, that she was there for the Reagan era that propelled the nightmare world I inhabit. But her world was one of nightmares too: two world wars, a pandemic, and the destruction of much of the US by industrialization.

Through it all, she painted rocks. No matter what happens, rocks stay the same. Rocks don’t let you down like people. Rocks, bones, flowers — those old reliables. Flowers won’t disappoint you if you don’t expect them to last. When they do, it is a pleasant surprise — especially in a wasteland, especially in The Black Place.

* * *

From The Black Place, we drove to Abiquiu, the land of O’Keeffe postcards and stationery. We hiked the colorful canyons of Ghost Ranch and drove the high road to Taos, where we saw the churches and pueblos O’Keeffe made famous to white people.

There is a two-fold comfort to Georgia O’Keeffe. The places she painted remain largely unchanged. And then there is the madness of her mind, which inspired her to escape into nature in the first place. Her diaries are full of spiraling thoughts, desperation for relief and meaning, awe and agony delivered without shame.

She wanted to show a cruel world something beautiful without lying.

I did not set out to retrace her steps. We had driven seventeen hours from St. Louis to drop off my daughter in Colorado, and we needed to fill a few days before we picked her up again. I made a list of places in northern New Mexico that I had always wanted to see. It was only in retrospect that I realized what I had done.

Once I knew, I embraced the journey. We headed to Plaza Blanca, or The White Place, the counterpart of The Black Place.

To reach The White Place you have to get the access code from the Dar al-Islam Education Center. The Dar al-Islam complex was built in 1979 and now holds the stark white badlands that O’Keeffe painted in the 1940s. It feels very American to have an Islamic center give me passcodes for territory visited over centuries by multiple groups. What’s one more, so long as they protect the scenery? These places never belonged to O’Keeffe either.

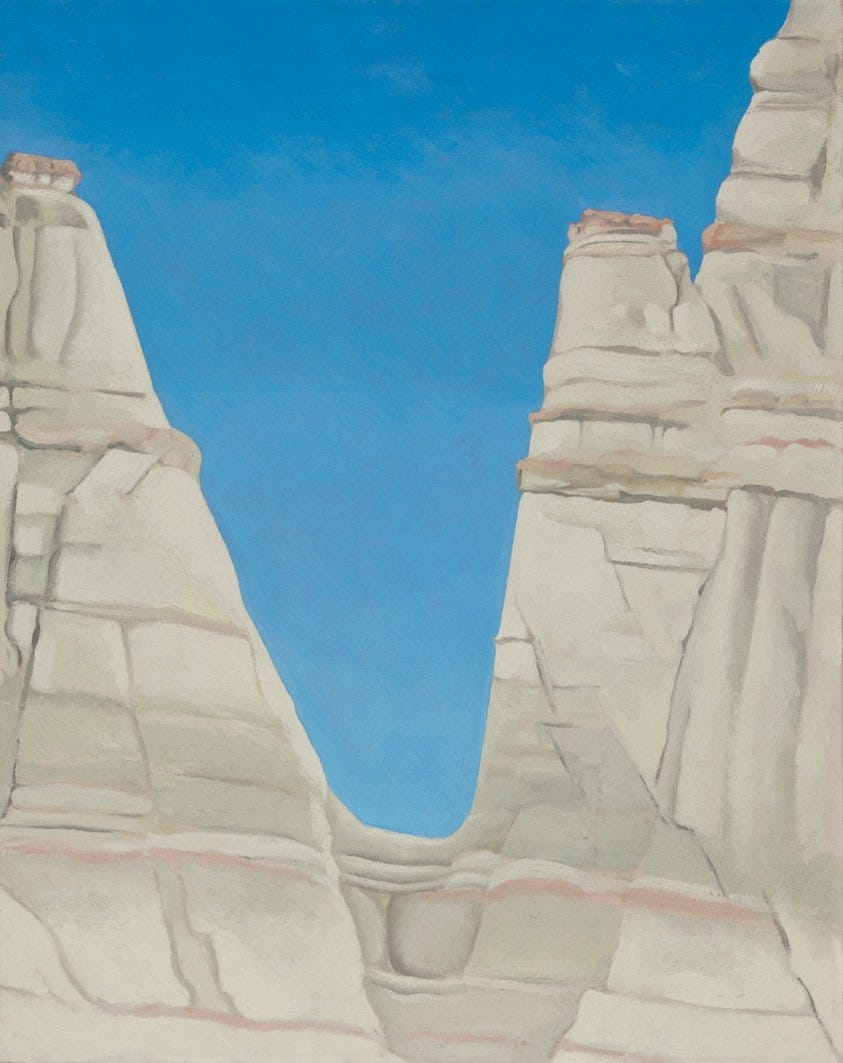

The White Place is supposed to be the sweet one: ethereal, calming. But I have never felt the sun beat as brutally as it did there. After following the formations from her paintings, we wandered too far in the desert and got lost. Everything in The White Place looked the same. I wondered how she painted here — how she found direction in a blank and barren world, how anyone could.

My son got us out by spotting a gleaming post on a cliff. We walked uphill, shaking with dehydration. When we reached the top, I collapsed in the shade and longed for the straightforward sorrow of The Black Place.

* * *

I am in The Black Place; I am in The White Place. I went to hell and bowed to its beauty. I went to heaven and got hurt by the light. I traveled to the places in between, and I treasured every minute I was alive, because I know it could all end by official decree.

And now, in 2025, it is.

When people ask me what I think of the Trump administration’s planned destruction of the US, I point them to the books and articles I’ve written over the past decade. I gave the historical context. I warned of the moves they’re now making. I explained the problems and offered solutions. Those solutions will no longer work, because people did not act in time.

“An enduring strategy of autocrats is to simply run out the clock,” I wrote in 2019. Did people not believe me? Do they believe me now that the political landscape looks like a Salvador Dali painting?

No one should resign themselves to this government’s malicious plans. But to keep our country, you must abandon old delusions. You must see The Black Place — and protect it, because there is beauty in truth. Even the darkest truths, the truths most difficult to reach and hardest to convey.

My mind replays my New Mexico trip like a subconscious rebuke. The paintings that guided it were made in similarly terrible times by someone who seemed like they had it all figured out, but inside was a wreck.

“I've been absolutely terrified every moment of my life,” Georgia O’Keeffe confessed, “and I've never let it keep me from doing a single thing I wanted to do.”

I wrote this article in July 2024. I waited until now to publish it, because I wanted to be wrong. No one enjoys watching their worst forecasts come to fruition and then be asked to rehash them after it’s too late. I wanted something akin to a spirit line to protect you from the future I saw coming. I wanted to protect myself too.

I saw The Black Place long before I laid eyes on it. It is humbling when the painted past meets the present. To know the wasteland is real, and that someone else saw it too, and loved it even in its wounds. That the love is as relentless as the pain.

“That’s a hill to die on,” I told my husband as we pulled away from The Black Place. It receded in the rearview, but the feeling remained. It is here now, guiding me through.

I’ve got lots of hills to die on, all over this country I love. It’s been ten years and I’ve seen too much and not enough. Sometimes I went on a road trip and sometimes I went on the run. Over time, the two merged, and became my life.

I took time to appreciate the hills I would die on — because I chose them.

* * *

Thanks for reading! I would never paywall in times of peril. But if you’d like to keep this newsletter going, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. That ensures every article remains open to all. Your support is greatly appreciated and needed!

Big news: I have a new book! The Last American Road Trip comes out in April and is available for preorder: www.thelastamericanroadtrip.com. If you like the travel and history articles on this newsletter, you will love this book! Tour information is coming soon. Stay tuned!

The Black Place, June 2024.

Black Place II, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1944.

More of the Black Place.

The White Place!

The White Place in Sun, Georgia O’Keeffe, 1943.

Inside a Navajo frybread shack.

Your love for this country as a place rather than a nation or an idea is very moving. Thank you.

Thank you. This one really connects. I’ve painted at Ghost Ranch a few times. O’keefe was a truth teller, like you.

And she painted lots of bones. And bones don’t lie.

I appreciate your integrity. A rare gift. And a high card.

My brilliant daughter was leading 27 scientists developing new cancer treatments until last month. Her division was shut down by Musk’s shutting off NIH. Her heart is broken.

I have no words yet to clarify my rage. I’m thankful for yours.