The Red, White and Blue Screen of Death

On the day the internet died, and the zombie internet returned.

Six days after one presidential candidate claimed he got shot and two days before the other candidate dropped out, the world ended, and everyone forgot.

I was on the road between St. Louis and Appleton, Wisconsin when the cyber breakdown hit. Appleton is the hometown of Harry Houdini, the magician who could escape anything: straitjackets, coffins, cops. During World War I, he registered as “Harry Handcuff Houdini” (real name Erik Weisz) and taught US soldiers how to elude captivity. He outran the hell of the world by devising his own hell and surmounting it.

It is a seven-hour drive from St. Louis to Appleton, mostly through Illinois — a jaunt by Midwest road trip standards. It is the rare drive that is almost impossible to make interesting, even though I am the easiest rider, dazzled by a sixteen-hour haul through eastern Colorado and Kansas culminating in a giant ball of twine.

The highlight of I-55 is a vitriolic soybean field describing your impending death in a series of rhyming signs. I like the field because it gives me novel ways to imagine my demise.

I’ve written two books about the nexus of government and organized crime. As a result, I live under a double bill of apprehension: They'll catch me too early, and you'll catch on too late.

It was a countdown summer, so I headed to Houdini Town to dream my death threats away.

But then it happened: the red, white and blue screen of death shut America down.

And for a few days, I wondered — was I free? Were we all? Or was this a new trap, the end of a game we never agreed to play?

* * *

We were in a truck stop in rural Illinois when we got word. There was no gas, the proprietor explained. Or rather, there was, but no way to get it into the car. Their machines ran on credit cards, and credit cards were dead.

A long line of people stood at the ATM, looking worried. Others looked vindicated.

Others felt vindicated but hid it, so that they didn’t look like an asshole. I know, because I checked my expression in the mirror multiple times. I bought sunglasses to block the knowing gleam in my eye. I paid with the cash I always carried.

Earlier that July morning, the largest cyber breakdown in history ground much of the world to a halt. American cybersecurity company Crowdstrike had installed a faulty update that caused over eight million systems using Microsoft to crash.

For one day, the dangers of digital dependency were laid plain.

In the US, thousands of flights were grounded, leaving the sky as blue and clear as September 12, 2001. Hospitals canceled surgeries. TV channels vanished mid-air. Companies sent employees home, unable to use their software or open their office doors. Supermarkets closed, as did chain stores relying on apps, until they could remember how to function like it was 1999.

The cyber breakdown was unevenly distributed. In some places — those not relying on the tainted software — life went on as usual. Not so for the regions of our route.

But we were prepared, because most of the Midwest is not part of the cashless world creeping into the coasts.

In March, I went West and was shocked by my inability to pay with cash and access basic services without apps. I had a traumatic experience attempting to order Dunkin’ Donuts from a peopleless purveyor near Pahrump, Nevada.

I wanted to raise Pahrump hometown hero Art Bell from the dead and tell him he was right. Humans had been replaced with robots and a faceless tech cabal monitored my glaze consumption.

“Traumatic” is perhaps overstating my Dystopia Donuts quest. But there is an uncanniness to having a site of happy childhood memories overtaken by your most absurd childhood fears. Et tu, Dunkaccino? Then fall!

There are folks who, if they could go back in time and give their younger selves advice, would tell them to buy Apple stock. And there are others who would tell their younger self to burn down Silicon Valley before it burns down the world.

* * *

I don’t buy a lot of stuff because I don’t have a lot of money. I don’t use a lot of technology because I don’t like it. I don’t like it because the people who control it are bad.

They ruined every good innovation of my life. They encouraged us to destroy the analog world, and after we did, they replaced it with bullshit and lies.

Google, once a wellspring of information sorted by chronology and preserved in caches, is an unusable cesspool. Photos taken by real people of real places have been replaced with AI fakes. Niche online hobby forums were sold to corporations and became unusable due to spam and bots.

The early excitement of reconnecting with old friends on Facebook was replaced by the relentless push of automatons. You reach out for connection, but the algorithm ties your hands. You follow friends but are instead shown influencers. Where did everyone go, and who are these made-up strangers in their place?

On YouTube and Tik-Tok, people transform their lives into infomercials, often to make cash in the gig economy that politicians deny exists. On Twitter, people become indistinguishable from the bots and paid operatives of political groups. Mobs spout vicious mantras in service of a cause or candidate that onlookers are told merits the cruelty inflicted on the last real human beings.

There is no safe place to talk to a friend. Privacy has been obliterated. Anyone can go viral, and virality, true to its early internet coinage, is a disease. You go viral in pieces, devoid of context, like a chalk outline at a crime scene. Your crime was existing.

Humanity has been stripped from the virtual world: deliberately, maliciously. The goal is to make humans less human. Less imaginative and more callous; more desperate and less kind. Less demanding of authority, but ruthlessly demanding of ordinary people who hold neither leverage nor power.

What you have left is your soul and they demand its surrender. They are molding the ideal fascist objects. I would say fascist subjects, but you are not granted even that level of autonomy. It is a mindset that they crave: gullible and groundless.

You are a pixel in the propaganda. You would be a cog in the machine but that’s too concrete. You cannot see the machinery, because then you would learn how it runs.

Cults thrive and truth drowns.

There is no way to opt out and still make a living — I’m here, aren’t I? This is where my words are published, but I don’t know if it’s where they will be preserved.

I watch site after site go down — decades of real-time news coverage erased. I watch movies and TV shows and music rendered abruptly inaccessible. History is a menace and imagination is a threat. Pop culture combines the two, creating a communal shorthand that defies political boundaries.

Pop culture is now considered dangerous. Billionaires want it destroyed even though it’s profitable. It’s not worth it to them anymore. It’s the wrong power, in the wrong hands — yours.

Your memories are the tech lords’ enemies. They seek to scramble history, erasing touchstones until you no longer recognize your world. They monitor you as an object but discard you as a person. You attract scrutiny, but not care.

So when the machine went down, I felt apprehension — but also, release.

* * *

By the time we stopped for lunch in Rockford, the cyber breakdown had spread. I got panicked texts from friends trying to fly to see ailing relatives, worried they wouldn’t make it.

I felt bad about my initial Luddite smugness. Life is hard enough, in a way often unspoken, without yet another shock.

We ate lunch at Johnny Pamcakes, a restaurant founded by a couple named John and Pam. We ordered enormous plates of pancakes — excuse me, pamcakes. The window of our booth looked out at desolate strip malls. But the homespun diner was humming, unaffected by the cyber breakdown.

It’s hard to break the Midwest because we’ve been broke so much already.

But at our hotel in Appleton, our apocalypse dodge came to a halt. The rooms used electronic key cards, which meant they did not open. If we wanted to enter, we had to find an employee to unlock our room with the one working key.

I asked a hotel worker if he had any clue when the cyber breakdown would end, and he said, “No idea, it could last forever.” I had asked workers this all day, and they became more forthright over time.

At an early stop at a chain store, employees were afraid to tell me what happened. Apparently corporate had instructed them to pretend all was normal. When I told them it was on the news, they relaxed and said “Yeah, we’re fucked, you should try somewhere else.”

At a later stop, workers had posted “cash only” signs and had tips for panicked travelers who only carried cards. Workers were resourceful and strangers gave cash to parents with small children so they could buy snacks.

What the day showed was the necessity of people instead of automation. People with ingenuity and compassion. People who could improvise in a way machines never could. People who kept the world together as technology tore it apart.

People who should be earning a hell of a lot more than they are.

We thanked the hotel staff for their help in tough times and left for our destination. We were in town to see my daughter perform in a string quartet. That night I watched her play a centuries-old song with such passion it moved me to tears. I thought of the generations of people who heard musicians play this song and who responded with similar reverence. How this song had predated and outlasted every technological change of the past two hundred years.

How this, in the end, was what mattered.

* * *

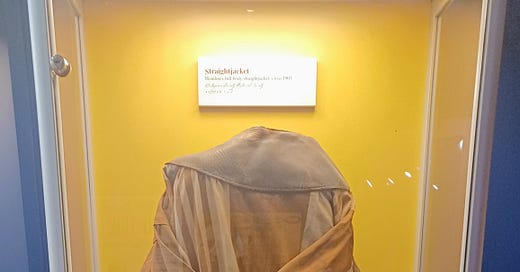

The next day we went to the Harry Houdini Museum, located in a former Masonic temple. The museum is full of traps and tests. Can you balance, can you lift, can you break free? I tried on a straitjacket and immediately cried to my husband to remove it, because the feeling it evoked was terrifying.

And familiar.

When Houdini wasn’t performing stunts, he was telling the world it was full of shit. His popularity coincided with the rise of “spiritualists” that took advantage of people’s sorrow to sell them lies. Frauds thrived in the 1920s in the aftermath of World War I and the Spanish Flu and the nationwide grief that had nowhere to go.

Houdini debunked the swindlers and fakes. Magic was real, he said. The world was full of it. But it was not supernatural. Magic came from the uniqueness of the human mind and its refusal to accept limitations. Theatrics are different than lies. Creativity is different from a con.

Houdini had an arrogant streak, and after daring an audience member to strike him repeatedly in the stomach, he developed peritonitis. He died on Halloween 1926. Born in 1874, Houdini witnessed empires crumble and pandemics spread and new technologies transform society faster than it could handle.

No wonder he felt satisfaction in having his own bag of tricks. No wonder he hated fakes with such ferocity. When there’s this much real pain in the world, you need a real balm to heal it. One created by man, not mimicked by machine, or exploited by imposters.

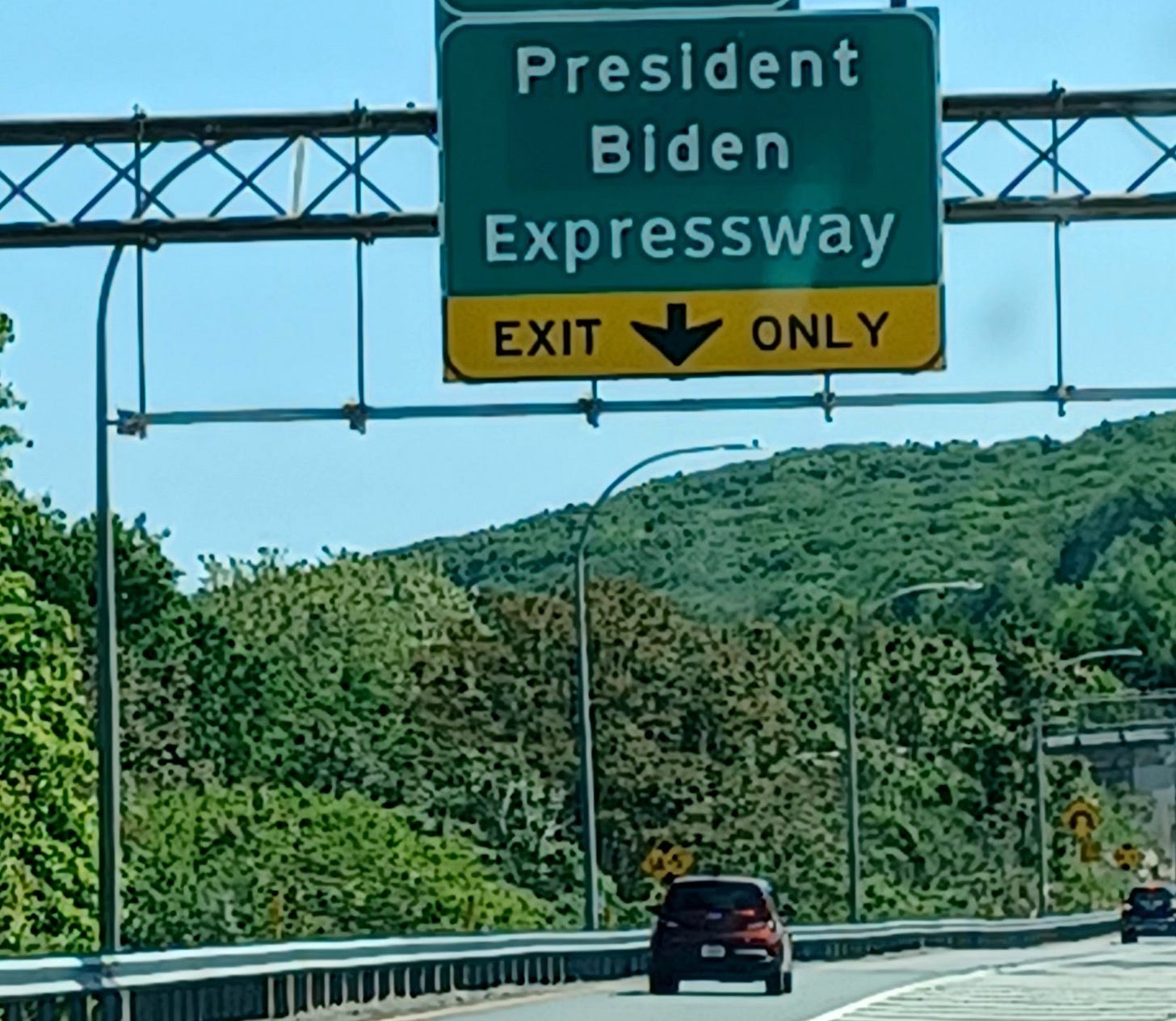

The next day we drove home. The cyber breakdown was gradually being remedied, but no one cared. As we passed the vitriolic soybean field, Biden dropped out. After the brief freedom of shock, the worst of the internet gathered, building new digital cults and cages.

And here I sit in invisible chains, dreaming of escape once more.

* * *

Thank you for reading! This newsletter is funded entirely by voluntary paying subscribers. That allows me to keep it open to everyone, and I don’t paywall in times of peril. This newsletter is also how I feed my family. If you like what I do, please subscribe!

Harry Houdini’s straitjacket.

“Embarrasses police to impress public!”

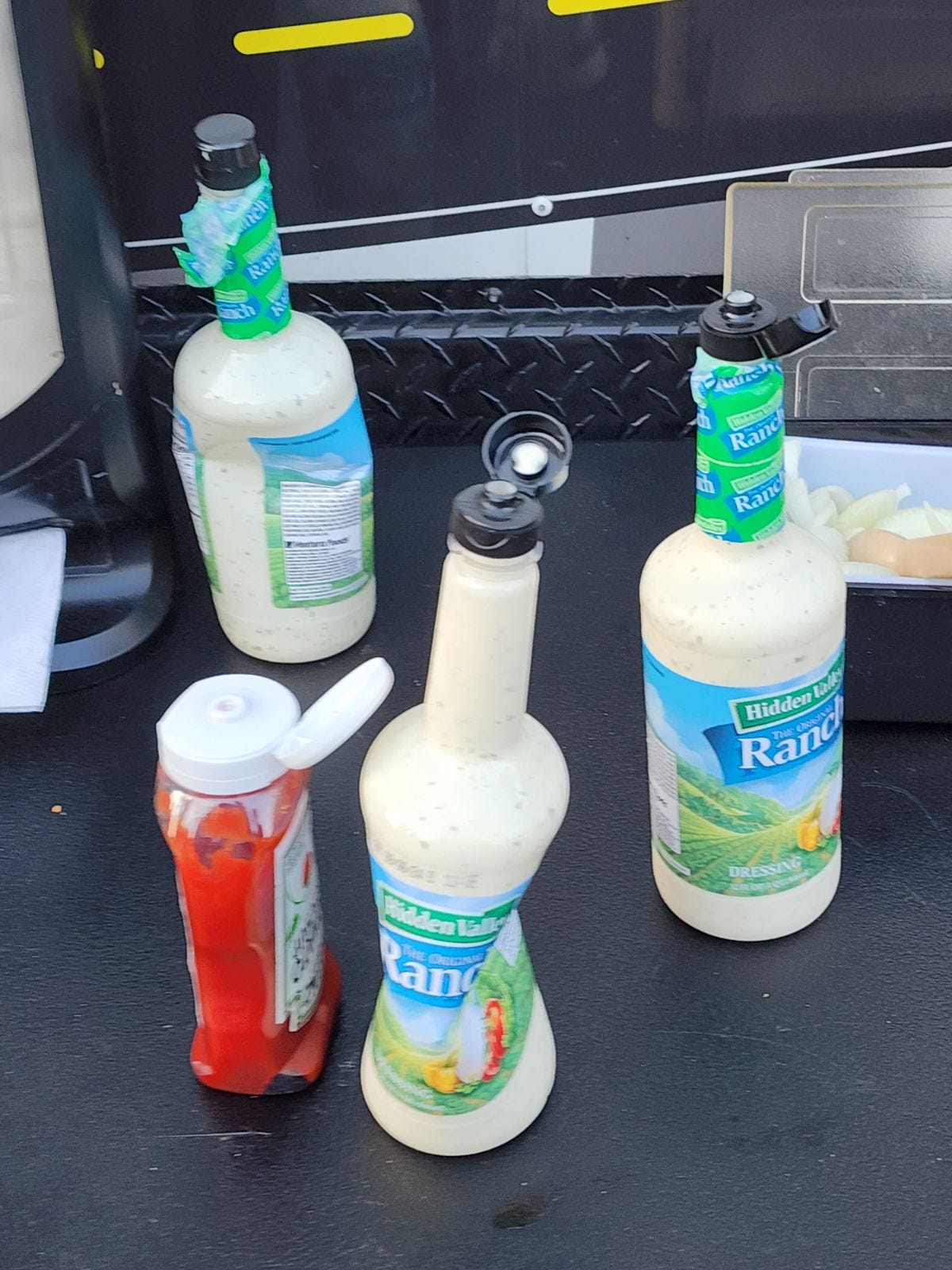

Proof I went to Wisconsin.

President Biden Expressway — Exit Only! (Photo taken in Scranton, PA, in 2023)

Attention subscribers: I am looking over page proofs of my book THE LAST AMERICAN ROAD TRIP this week (preorder it here!) I’m not sure how long this will take me. I’ll probably have a new article next week anyway, but if I don’t, that’s why. See you soon!

I would invest in carrier pigeons just to read your words.

“The real problem is not whether machines think but whether men* do.”

-B.F. Skinner.

*Update: people